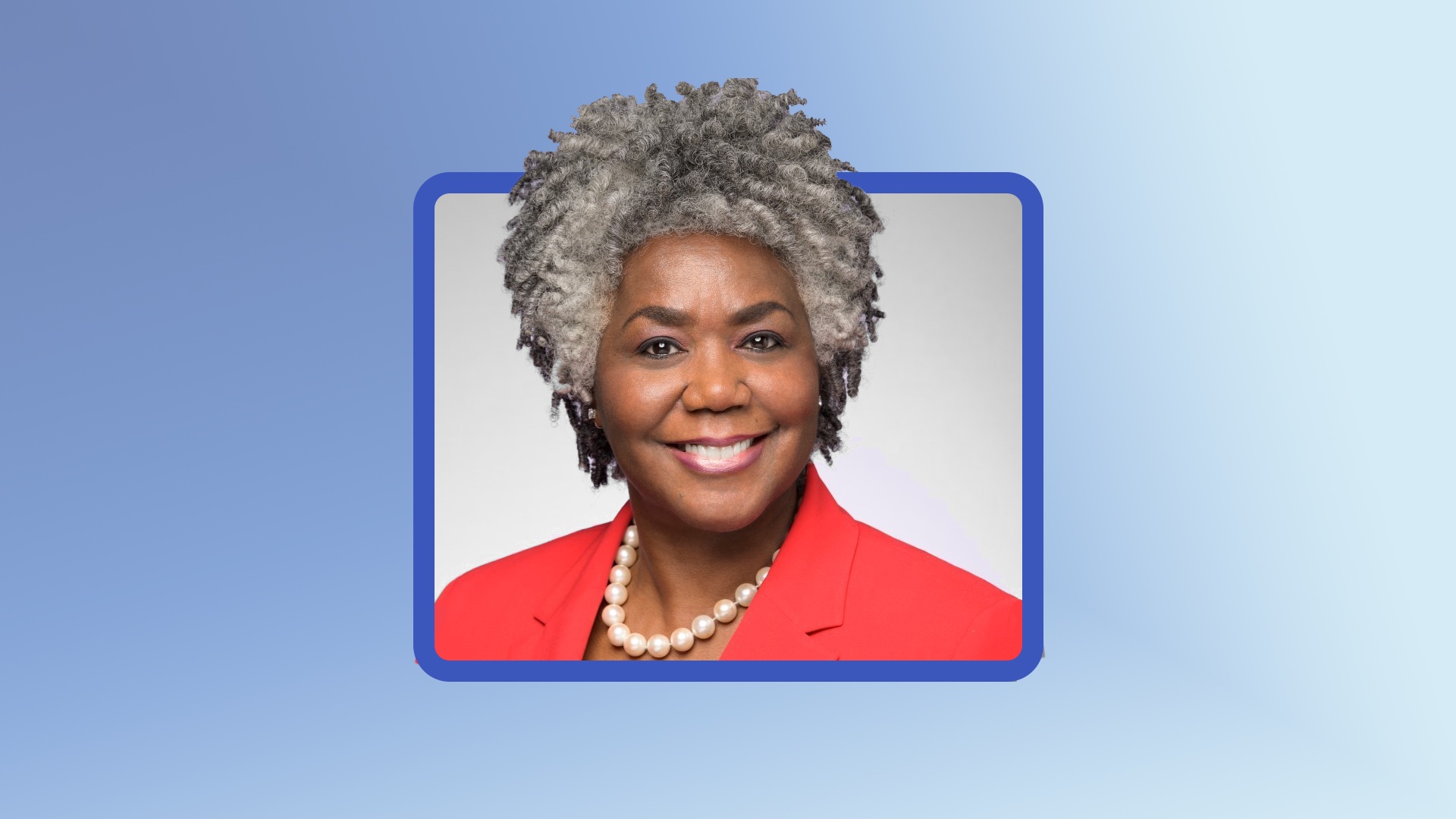

On an overcast afternoon last fall, Khaleigh Reed stood with crowds at the University of Colorado Boulder football stadium. She had transferred to the school the year before and had been feeling “kind of alien.” The game ended, and she stood talking to people she’d only recently met. As the skies opened into rain, the crowd spilled out of the stands and onto the grass, and she and her new friends joined them, laughing together and running with the large gathering of students.

For Reed, a senior journalism major who had transferred from a community college at the start of her junior year, the moment felt cinematic.

“I’d hit it off with these two people at the game, and we were all, like, excited and happy,” she recalled. “I had this sense of relief, and with the rain and friends and community all running onto the field, it was like the feel-good end of a movie. After everything I’d been through, I was able to find some happiness.”

Months later, that memory would become an actual scene, the emotional center of a three-minute digital story Reed created as part of a pilot project housed at C.U. Boulder’s Renée Crown Wellness Institute. The project invited more than a half-dozen undergraduate students to craft multimedia narratives about their own experiences of “flourishing” — a positive term the institute uses without rigid definition.

Reed’s experience became part of a prototype for a new digital storytelling initiative being designed by the Crown Institute to be shared with educators the Flourishing Academic Network, or FAN, a consortium of universities committed to advancing wellbeing in higher education. At one level, the project was intimate: nine undergraduates meeting over six sessions, workshopping drafts and learning how to shape a story that could be shared aloud. At another level, the project was taking shape as the infrastructure of something larger. What unfolded in those rooms would eventually be distilled into a physical toolkit — a carefully designed, printable and digital guide intended to help other campuses create similar spaces for student storytelling.

“One of our aims is to elevate youth voice,” said Michelle Shedro, a researcher at the Crown Institute who helped lead the project and design the toolkit. “Not just as an outcome, but as a way of doing the work. Tapping into youth voice is both a tool and a goal of ours.”

A Container for Voice

The digital storytelling pilot grew out of a broader question the Crown Institute has been asking for years: How do students themselves understand wellbeing?

Founded in 2018, the Crown Institute conducts interdisciplinary, participant-based research on youth and adult wellness. Its work spans maternal mental health, K-12 education, and campus-based initiatives such as Mindful Campus, a long-running program that offers courses and programming for students, faculty, and staff. But the digital storytelling project marked a distinct turn — one that placed student voice not only at the center of the findings but at the center of the method.

Rather than asking students to respond to surveys or predefined frameworks, the institute invited them to tell stories — in their own voices, with their own images, shaped through a guided but flexible process of storytelling in multimedia form.

“Digital storytelling is very adaptable to various disciplines and topics. People have many different ways of telling their stories, and it’s really dynamic and fun,” Shedro said. “So we wanted to give young people the tools to do this, and we also wanted to be able to learn from what they create around the question: What does flourishing mean to you?”

In this way, the project is both research and invitation, said Jenna Bensko, the outreach and education project manager at the Crown Institute. “When we create the container — the opportunity — and when students feel a sense of belonging, the flourishing happens.”

To facilitate the pilot, the Crown Institute partnered with faculty from the University of Colorado Denver, including Marty Otañez, an associate professor of anthropology and a longtime practitioner of community-based digital storytelling. Otañez described the work less as teaching students how to edit video and more as helping them learn how to land a story. Over six sessions totaling 24 hours, students moved through a carefully sequenced process: journaling and free-writing, story circles, writers’ workshops, and storyboarding before ever opening editing software.

The early sessions focused almost entirely on building trust — learning one another’s names, sharing fragments of ideas, listening without rushing to respond. “The soul of the process is community,” Otañez says. “You can’t shortcut that.”

Only later did the technical work begin: recording voiceovers, selecting images, and learning DaVinci Resolve, the editing platform used during the pilot. Even then, Otañez emphasized restraint. Images were meant to deepen meaning, not illustrate every noun. Metaphor mattered more than polish. But at the core of it all was each person’s choice of a story, which for Otanez is part of the rich process of discovery and reminder to always expect the unexpected.

“Some of the things surprised me, and this is always the case. Some students are really quiet and maybe a little reserved, and so we never know what we’re going to get,” he said. “And then sometimes their stories are just so rich because with their introversion, they’re thinking so much and so deeply, and they come up with these beautiful pieces.”

The Crown Institute’s framing of flourishing provided a lens, not a script. Students were encouraged to ask where flourishing appeared in their stories but not required to prove that it did.

The nine students who participated came from across campus — political science, finance, health sciences, journalism. Few had prior experience with digital storytelling. Some arrived with clear ideas, and others discovered their stories only after listening to their peers.

Reed remembered one classmate who shared a story about a serious health crisis — hospitalization, uncertainty, learning to live with a chronic condition. “You would never have known just by looking at them,” she said. “That really stayed with me.”

The story circle, where students read drafts aloud and receive guided feedback, became one of the most powerful sessions of the pilot. “It was like journaling,” Reed said, “but with a community.”

Students learned not only how to receive feedback, but how to give it — asking questions that clarified rather than corrected and noticing what lingered emotionally rather than what could be fixed mechanically.

One thing that interested both the facilitators and the Crown Institute organizers was the nuanced way the students seemed to accept that flourishing was a work in progress, found as much in small moments as in large ones.

One student used hair-braiding as a metaphor for independence and belonging. Another traced academic growth through mountain climbing. Others spoke about illness, procrastination, loneliness, or the quiet relief of finding a place to stand. The stories that emerged resisted tidy conclusions.

What unified the stories was their honesty, and the facilitators had to respond without an agenda. “We were very careful not to force the message into the stories,” Otañez says. “Otherwise you lose the essence.”

That tension — between institutional goals and individual truth — shaped the project throughout. The Crown Institute’s framing of flourishing provided a lens, not a script. Students were encouraged to ask where flourishing appeared in their stories but not required to prove that it did.

“In a lot of higher ed discourse, we focus on how hard things are,” Shedro said. “That’s real. But we also wanted to create space for hope, without denying complexity.”

At the end of the pilot, the group gathered for a small screening event. Friends, faculty, and family members attended. Each film played, and each student spoke briefly about the process. Audience members noticed things the facilitators had missed — small gestures, lines that echoed, moments that felt larger than intended. The narratives developed lives of their own in the eyes, ears, and minds of the audience.

“That’s always what amazes me about storytelling,” Otañez said. “Once the story leaves you, it becomes something else.”

Beyond the Pilot

The digital storytelling pilot at C.U. Boulder was never intended to remain a one-off experience, contained within a single semester or a single group of students. From the outset, the Crown Institute team understood the pilot as a way of learning how to design a methodology that others might eventually adapt. Out of that work, a digital storytelling toolkit is emerging, one intended to be freely available as a PDF for use across the FAN consortium. The toolkit is not a script or a curriculum to be followed verbatim. Instead, it offers a flexible framework shaped by what unfolded during the pilot itself.

“We observed everything,” said Shedro, who led the writing and design of the toolkit. “What worked, what stalled, where students needed more time, where they needed less.”

The resulting document is organized into three broad units: an introduction to flourishing and digital storytelling; guided opportunities for writing, story circles, and reflection; and hands-on production work, including storyboarding and media assembly. Throughout, the emphasis is less on technical mastery than on process — listening, revising, choosing what to include and what to leave out.

There are recommended minimum hours, suggested facilitator ratios, and sample prompts, but little insistence on uniform outcomes. That was intentional by design.

“We wanted something that could live in a lot of different contexts,” Bensko said. “A semester-long course. A co-curricular program. A student organization. It needed to be adaptable.”

That adaptability reflects a central insight of the pilot: the definition of flourishing can’t be standardized any more than the stories that attempt to capture it. Some students told tightly framed narratives about specific moments. Others traced longer arcs — from illness, from isolation, from uncertainty toward something steadier but unresolved. The toolkit preserves that openness, encouraging facilitators to resist steering stories toward predetermined conclusions.

But equally important, Shedro noted, was laying the groundwork for collaboration — the time spent building trust and guiding students in the most effective ways to be active listeners and give constructive feedback.

In FAN meetings, interest in the toolkit has already begun to circulate, though the Crown Institute team has been careful not to rush its release. For the students who participated in the pilot, the toolkit is beside the point — a downstream product. What stays with them instead are the stories themselves and the experience of being trusted to tell and hear them.

For Khaleigh Reed, soon to enter the field of journalism, the potent experience with multimedia storytelling became further evidence of all you don’t know about a person unless you ask questions and listen well.

“You never know what someone’s going through,” she said. “This project gave us a way to see that.”