Philip Glotzbach’s new book Embrace Your Freedom: Winning Strategies to Succeed in College and Life has as many lessons as it does audiences. As its title implies, it is written primarily for graduating high school students anxiously hovering between post-admissions and their first year of college, but it also speaks to their parents, who will undoubtedly read along, with advice about letting go that is not always easy to hear. Those in the field will connect themes such as “why are you going to college?” and “fall in love with your fallback school“ with some of the biggest challenges in higher education today such as skyrocketing tuition, inflated rankings, and student wellbeing.

With a non-didactic tone, Glotzbach combines the experience and authority of a college president with the hindsight and candor of one who no longer holds the title. His advice to first-year students on making the most of this seminal period has a fair share of practical information, as well as wisdom rooted in philosophy, developmental theory, and political science. As he writes plainly about personal responsibility and pride in achievement, he reminds students we are all shouldered by our communities. Perhaps most distinctive is Glotzbach’s message about freedom itself, something students may first take to be about the absence of external controls, but which the book quickly clarifies as the joy that comes from setting and reaching goals that align with who you are as a person. His book is available for pre-order now (Simon & Schuster, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Post Hill Press, etc.); its publication date is July 9, 2024.

You have been in academia for decades and a college president for seventeen years. What motivated you to write this book and what are your hopes and dreams for it?

I wrote it, frankly, as a labor of love. Over my career, my greatest pleasure came in seeing how undergraduates develop both intellectually and personally over those four years. It was especially satisfying to see that transformation reflected through the joy in their parents’ eyes. This book came out of talks that I gave to new students and parents every year at Skidmore in which I offered my best advice about how to realize this promise of a college education. Following those talks, I would repeatedly get asked for copies of my remarks – which I never really had available to share in any formal way. So, I knew I wanted to capture those exchanges in some fashion.

In the book, I approach that same audience in a conversational way – not to preach at them or talk down to them, but to talk directly to them in a way that is accessible. At the same time, I wanted to have enough substantive content in the book so that, if a college decided to use it as the common read for the incoming class, faculty members could actually enjoy teaching it. It isn’t just, “Hey, here’s how to do your laundry.” Frankly, I’d love for people to review Embrace Your Freedom and say, “This book should be required reading for all new students.”

You have many important messages in the book, but what would you say is the overarching theme?

I’ve always believed that what students most need coming into college is just to pause and think about where they are at this stage of their life and how to take charge of moving forward toward where they want to go. That’s a major theme that recurs throughout: You’re in charge; you’re responsible for your life. What does that mean? You’re responsible both for what you think and for what you do. I’ve always thought those ideas are very important for new students to consider.

I think they’re even more important today for a couple of reasons. So many students go through such a frenzy getting into college. It’s just such an anxiety-producing experience with too many thinking that if they didn’t get into their first choice school their life is over. What I am trying to encourage young people to do is look beyond all that, come through to the other side of that angst, and embrace what’s about to happen to them – and a lot of it is going to be very positive. But this is a very anxiety-ridden generation. They have been really closely engaged with their parents (or their parents have been engaged with them). Their parents have probably organized their lives in a very directed way over the years, and with all the right intentions. Given this background, and particularly coming out of COVID – which really threw a monkey wrench into their educational process – I think that the messages in this book are especially important for this generation.

“Going to college should be an intentional project – not just the expected next step after high school.”

Now, all of a sudden, they’re away at college. What are they supposed to do? And how are they going to do it! I remind them that they are in charge of their life, even if so many cultural and social forces have been telling them that they’re not – even if people have been telling them that they’re victims. Ultimately, they have to take charge of their own life if they’re going to realize the opportunities that are before them. This book makes that case and offers a lot of practical guidance about just how to do so. It suggests ways to deal with the sometimes scary aspects of that freedom.

Given what you’re saying, it is not surprising that you wrote the book for both students and parents. Do you also have a strong message for them?

The two chapters for parents are, first, how to partner with your student and, second, how to let go. And I’ll come back to those chapters in a moment. I’ve always intended to include parents in this book because, when I was giving those talks at Skidmore, they were sitting there too. I very much wanted them to hear what I said to the students. Now I want parents to read all the student chapters, because they tell a coherent story about what their students should be focussed on as undergraduates: understanding some key concepts (like freedom, liberal education, etc.), making big plans, following through to execute those plans, taking good risks, understanding the ethical dimension of their lives, and winning a “victory for humanity.” Parents have always had an enormous investment in their kids’ lives, but even more so today. One crucial role they can play now is to reinforce these ideas with their kids.

And of course, today’s parents have their own questions. How do they navigate the (probably) unfamiliar landscape of their kid’s college? How should they engage with all those different people who are there to try to help their student, without being overly intrusive in their kid’s life? I try to help them think through these issues, in the context of partnering with their student. It may sound paradoxical to say partner and then let go, but the idea is for their partnership with their child to evolve – to take a new form that’s more appropriate for the relationship they will have post-college. So, one of the most important chapters is about letting go and how to do it, while acknowledging that it’s not easy.

For one thing, we all know that college is enormously expensive. Many parents are literally mortgaging their lives to pay for it, and they want to make sure that this train isn’t going to go off the tracks. And what if it does? Parents are in closer communication with their kids today than in the past. So, if their student is having trouble, they’re likely to hear about it. How should they react to that situation? What’s their appropriate role? Part of what I’m saying in the parent section is, “Give them the space to handle their own problems to learn from those experiences.” But there are times when it is appropriate for parents to become more active in working with the school. I give some very practical advice here as well, such as: “Contact the school at an appropriate organizational level. I.e., don’t call their professors; don’t call their roommate’s parents or the RA in their residence hall.” The primary message is: “Don’t get between your student and the people they should be working with on a day-to-day basis.”

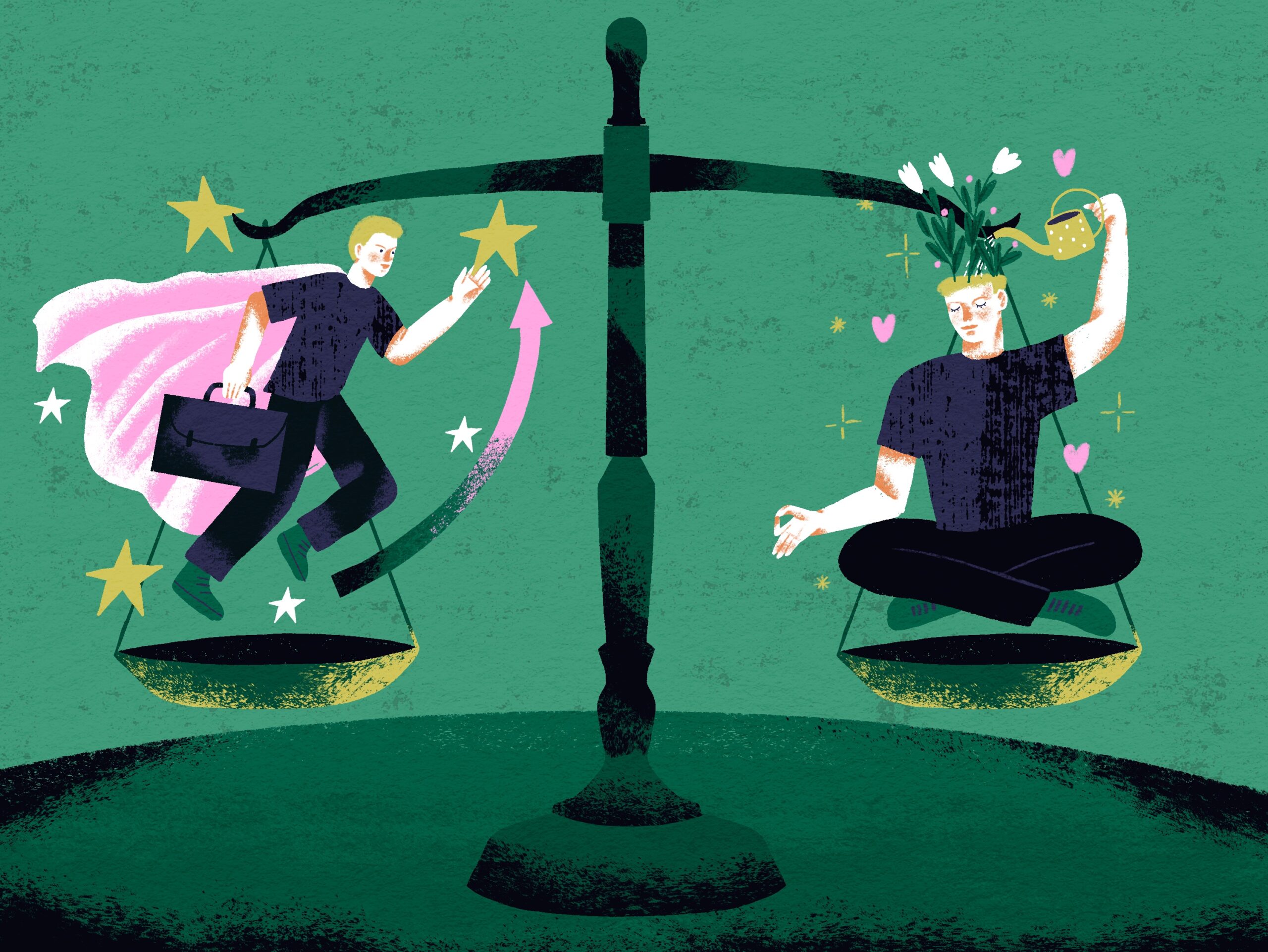

Can you explain the title “Embrace your Freedom” – it’s not what most people, particularly students, would think, is it?

For the traditional age student, when you go off to college, all of a sudden you have a lot more freedom or autonomy than you did even a few months ago. But becoming a mature, fully-functioning adult doesn’t happen automatically…or overnight. There’s a lot you have to learn and go through. And so my contention in this book is that if you start off thinking about some of these ideas – beginning with the concept of freedom – you will be better positioned to do the work of becoming a mature adult.

“You’re in charge; you’re responsible for your life. What does that mean?”

That’s why I talk about two different ways of interpreting freedom – beginning with the “negative interpretation,” which is just the absence of constraints. Which is our typical way of looking at it, right? Freedom means nobody’s telling me what to do. Well, that’s fine; it’s important. But the more meaningful and mature concept of freedom is what I call the “positive interpretation,” which is freedom as self-regulation. It requires taking charge of yourself and deciding what you want to do and how you do it, which is more difficult than just throwing off the constraints of your earlier life.

In the book, I quote the Eastern European physician and poet Miroslav Holub, who says that “a marathon runner is more free than a vagabond, and a cosmonaut than a sage in a state of levitation.” To be a marathon runner, you have to devote yourself to an extended program of intense training and preparation to get ready to run your race. It requires a whole lot of self-regulation. But when you get to the point where you actually can run 26.2 miles, you experience a level of freedom or ability that you never would’ve had if you hadn’t put in all that work. And the second part of this message is that you’re necessarily doing this in the context of a community. You can’t do these things alone. And that fact, in turn, entails certain obligations to that community.

The notion of embracing your freedom really has to include this positive sense of freedom. And as you go through the book, that idea recurs as a motif. Every time I talk about taking charge of this or that aspect of your life, it’s another example of embracing your freedom. So again, it’s moving beyond the limited conception of freedom in which you no longer have anybody to tell you what to do, and finding out what it is that you want to do. What are your goals? What are you trying to get out of this college experience? Then what do you need to do to accomplish those objectives? What sequence of events has to occur? And, by the way, what does all that have to do with your decisions about drinking and sex and other aspects of your life (e.g., eating well and getting enough sleep)? How do those choices affect your ability to do the things you most want to do?

I also say to the students, “Look, you don’t have to have all the answers right away. You don’t need to have worked out all your big plans in your first year – and certainly not in your first semester/quarter. And be prepared to change your mind as you go along. But do start thinking about all this from day one. In Chapter 9, “Begin Now!” – which I think is one of the most important ones – I urge students to realize that their college career begins on that very first day. Not next semester or quarter. Not next year. That’s a good moment to begin thinking about where you want this journey to take you.

One of the most vivid ways to do so is to envision yourself at your college commencement, the beginning of the next phase of your adult life. At that point, as you look back over your undergraduate career – and as people are asking you questions about how you’ve spent your time – what will you be proud of? What might you regret? What will you have done to gain the maximum benefit from this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity?

One of the questions you ask students upfront is “Why are you going to college at all?” – what are you getting at here?

Going to college should be an intentional project – not just the expected next step after high school. So ask, “Okay, just why am I going to college? What do I hope to get out of it – especially given what it’s going to cost in time, energy, and money? How do I expect my college education to help me move to the next step in my life?” Again, it’s not at all necessary – or likely! or even desirable! – to have all the answers at this point. And whatever answers you might have are likely to change. But it really helps focus your mind to ask these questions – and to realize that there are other options (e.g., a gap year, military service, volunteer service, trade school, and many others). Let’s be clear: I’m not in the least trying to discourage anyone from going to college. But they will be much more likely to succeed – to come away feeling proud of what they’ve accomplished – if they do it on purpose.

Why do you begin, in Chapter 1, with liberal education?

This book emphasizes the various dimensions of what an undergrad career should offer to students. The first chapter talks about the power of becoming broadly educated. For one thing, this outcome is enormously important if one is to thrive in the professional world today’s graduates will be entering. I include several stories of students I have known whose life pathways illustrate this point. For example, one young man who initially wanted to be a writer ended up working on the New York Times’ digital site as a senior software engineer. Today he’s running his own software company. He didn’t study computer science in college, and he certainly didn’t think about it as a potential career. But he gained a broad liberal education, and above all he learned how to keep learning.

My argument is that in the context of today’s professional world, the more narrow your course of studies in college, the shorter its shelf life. Because when you get out there, the professional world is going to continue changing. It’s evolving at a pace that is hard for any of us to wrap our heads around. So, you have to be intellectually flexible. You have to be able to access – and synthesize – knowledge and information from a variety of areas. And once again, you have to be able to continue learning.

In sum, the traditional skills you learn in a liberal education will set you up for life: critical thinking, reading, drawing upon different areas of knowledge, understanding how different areas of inquiry create knowledge in their own ways, appreciating what different cultures have to teach us and valuing the humanity of people who might present as being different from us, developing your creative imagination and the capacity to communicate effectively, and so on.

“Colleges and universities don’t just create personal good. They also create social good.”

Another idea I emphasize is the value of studying a subject – choosing a major, minor, or concentration – that inspires your passion. If passion drives what you’re doing, you’re more likely to excel. Studies have shown that students who choose a major based on their interests do better in college (and they do better in the rest of their lives, as well!), as opposed to students who choose a major just because they think it’s going to get them a well-paying job. Choose a course of study based on your interests so you can really get into it and get the most out of it. Be fortified with the complementary capacity to think broadly. Then you’ll be prepared for whatever the professional world throws at you.

You talk in the book about the responsibility of becoming a good citizen as part of a student’s education. That’s not always the first thing today’s students are hearing from their administrations.

As a college or university president, it’s easy to succumb to the temptation of saying “let me tell you about the great jobs our graduates are getting.” That’s not unimportant. Sure, we want our students to be gainfully employed. But if that’s all we are saying, we’re ignoring the other critical goal of a college education, which is why the second half of Chapter 1 addresses the topic of citizenship. And why I quote Thomas Dewey who wrote, “Democracy needs to be reborn every generation. And education is its midwife.”

Colleges and universities don’t just create personal good. They also create social good. The people who graduate from colleges and universities in this country become citizens of our democracy, often leading citizens in both private and public life. And, in fact, the intellectual abilities and knowledge that position a graduate to thrive as a professional are precisely the same as those required to function as an informed, caring, and responsible citizen. We need them to do so today, perhaps more than ever before. So, as I’m advising students to become intentional stewards of their own education; I am also challenging them to educate themselves to become effective citizens of our democracy.

And what does that mean? You should be able to participate in political discussions in a constructive way, including listening actively to what someone else is saying, and not just shouting across the room at them. You should be intentional about accessing good sources of information. You need to know what it would take to change your mind on a given political topic. And college should be the best place to develop those skills. If you look at the mission statements of most colleges and universities, you’re likely to find some reference to responsible citizenship or leadership. But that doesn’t mean those values are automatically prominent in the experience of their students.

So, what I’m saying to students is, “Yes, it’s really important that you prepare yourself for the professional world. But it’s equally important – and in some ways, even more important – that you prepare yourself to be an informed, caring, responsible citizen. And you may have to do that work yourself. Your college or university may not show you what you have to do. But if you pay attention to what I’m talking about in the book, you will be well positioned to claim that part of your college education as well. You will graduate as someone well prepared to participate as an effective, caring, responsible, informed citizen of our democratic republic.”

You have two chapters dedicated to wellbeing – one on the body and one on the mind – and it also seems to be a theme woven throughout the book. What are some big takeaways there?

One of the places where I really expanded the book (beyond those original talks) was in thinking about the notion of wellbeing. I have no illusions that any book for new students will “fix” all their problems or guarantee they won’t make some mistakes along the way. That’s just part of what happens at this stage of our lives. What I am trying to do, however, is first, to provide as much science-based information as I can about a range of topics relating to physical and mental wellbeing. And second, to encourage students to use this information to make good choices as much as they can…and to get help when they need it.

I also bring up the subject of happiness. There’s been no shortage of commentary about happiness in popular culture, and it’s very much on the minds of today’s students. But it’s so important to realize that genuine happiness – as opposed to, say, pleasure – is elusive. If you pursue it, it’s likely to run away from you. And you’re not going to catch it. The way we become truly happy is by finding a purpose in life and doing meaningful work with other people. That’s how we make it possible for happiness to find us. So that’s why I encourage college students to think in those terms – to find a cause to embrace (along with their freedom). Chapter 8, specifically, talks about giving back and paying it forward. I tell them that, as a college graduate, you’ll be part of approximately 40% of the American population who has a bachelor’s degree. Only 40%. That alway sounds like a pretty small number to me. And if you look to the world at large, there are about 8 billion people out there, and probably fewer than 10% have a college degree. This means you’re in a position of privilege – not entitlement, but privilege – just by virtue of having this opportunity. So my challenge to students is: “What are you going to do with it?” Or, as I asked before (quoting Horace Mann), “What ‘victory for humanity’ are you going to win?” This is a question all of us should consider, but it’s particularly relevant for college students. If we go to college to realize both personal and social goods, then it’s incumbent upon us to ask: “What am I prepared to do to leave the world a better place than I found it?”