LearningWell Editor Marjorie Malpiede talks with Beth McMurtrie of The Chronicle of Higher Education about new research on A.I. and student cognition.

Category: Teaching & Learning

Examining innovations that help young people thrive.

A New President Strives to “Go Beyond”

John Volin, Ph.D. is the new President of Gustavus Adolphus College, a small liberal arts school nestled in the scenic Minnesota River valley town of St. Peter, Minn. In his convocation address, Volin told his fellow “Gusties” that being there reminded him of his upbringing in South Dakota — of the rural roots that shaped him and his desire to pursue higher education in the first place.

“We are not just beginning a new school year, we are beginning a year of discovery, growth, and possibility,” he said, revealing his signature optimism. Before leading Gustavus, Volin, an environmental scientist, was provost at the University of Maine and, prior to that, vice provost of academic affairs at the University of Connecticut.

As a long-time college administrator and frequent first line of defense against external threats to higher ed, Volin might be less zealous about assuming a role many others are exiting. Instead, he says he has taken to heart Gustavus’ new slogan — “Go Beyond” — which for him means focusing on what’s possible, even as you manage what’s facing you. Volin has long hoped to lead an institution that would align with and benefit from his robust body of work in student-centered, transformational education. In Gustavus Adolphus, which is guided by the Lutheran mission to educate students with purpose, he has found it.

In this candid interview with LearningWell, President Volin talks of first impressions, early priorities, and how college can be a pathway to life-long wellbeing.

LW: You are a first-time college president at a very challenging time for higher education. What keeps you so engaged and optimistic?

JV: I was reminded just the other day of why all of this is so important. A couple weeks ago, we had our first-year students arrive with their parents. There are all the hugs, the occasional tears. And you see this new cohort of students that have this energy, this curiosity. They’re nervous, maybe even scared, but they have all these aspirations as well. And it really reminded me of the awesome responsibility that we have — this privilege to help shape the conditions that are going to allow those students to thrive, not just during their undergraduate years, but well into the future. And that is something that gets me excited and keeps me engaged. It was the reason I got into higher ed in the first place.

LW: What drew you to Gustavus? And how does the culture here resonate with your own philosophy on learning?

JV: I grew up in the upper Midwest, so I knew of Gustavus and remember being intrigued by its residential liberal arts setting. As family tradition, we all went to South Dakota State University, and I’ve always been in public comprehensive research universities. So when Gustavus first reached out to me to throw my hat in for president, I was like, ‘Oh, this is exciting.’

But the mission to educate students to lead purposeful lives is what resonated deeply for me. The Lutheran tradition, similar to the Jesuits, is to educate the whole student — mind, body, spirit — and that is really alive here. It’s more than a slogan. It really is part of the core, and you can never take that for granted. I think there is a real motivation for faculty and staff to mentor our students beyond the classroom — to help them develop a sense of belonging, a sense of community, to give them agency and character development to lead lives that contribute to society. That’s what really drew me here.

For me, this opportunity has been a long time coming. Early in my career, I started to see this huge responsibility we have to focus on the formation of our students as human beings. And data is starting to really show the benefit of that in terms of life-long wellbeing. It really does make a difference when students know that they’re cared for — that they belong — even as we challenge them in the classroom. And then we need to open up opportunities for students to be able to take what they’ve learned in the classroom and get a really authentic experiential learning engagement. Whether it’s through an internship or research experience or service learning, we know that those high-impact practices lead to overall wellbeing during the undergraduate years and well beyond. These students tend to have a higher chance of flourishing later on in life, have greater career satisfaction. And so that for me, is a real driver.

LW: Can you describe an example of this type of approach?

JV: Let’s take curriculum development. I have been a part of two very large university curriculum redesign initiatives. And yes, it’s exciting to make change, but often it’s been incremental change — over a six- or seven-year period. And it’s always compromise after compromise, and no one really feels completely great about the product. But here, the faculty and staff came together and, in an eight-month period, redesigned their curriculum into a really innovative model: A third of the students’ credits are in their major; a third are in general education; and a third are in electives. So it allows for that depth that the students need and but also the breathing room to try new things. And the results have been really exciting.

My wife Valaria and I live on campus, and every night, we walk our dog — our 15-month-old golden retriever named Sofia. Invariably, our half-hour walks turn into 45 minutes to an hour because we end up talking with students, and I noticed that I would get very different answers to the typical question: “What are you majoring in?” Students will say “business and music” or “biology and theater,” and I love it because that’s what a true liberal arts education can offer. They are using their whole brain.

LW: What are some of the big things you’re working on?

JV: There’s amazing momentum here, but we can’t just be the best kept secret. We need to better define and communicate what we do. There’s been a lot of work done in marketing and communications, and our new brand, which I was introduced to this summer, is “Go beyond.” I love it because it’s an action phrase that can mean so many things: “Gusties go beyond.” “Go beyond the Hill,” which is what campus is often called.

That’s part of a new strategic visioning and planning process I just announced at convocation. By the way, they tell you as a new president, you should never do a strategic plan your first year, and yet here we are. Actually, this was a mandate coming in, so it’s perfect timing. We’re looking at this as a significant opportunity to shape the institution’s future with purpose and collective ownership. It’s about who we are and where we want to go, and it involves all members on campus. We will ask ourselves: What do we do well? Where must we do better? What can we imagine that doesn’t yet exist?

LW: Do you think your message about the student-centered work you are doing here will resonate with the public at a time when there is so much skepticism on the value of a college degree?

JV: I hope it will. I think, historically, higher education has isolated itself too often from the public. But when you’re on a college campus, at least in my experience, it doesn’t always feel that way. I think we can all agree that we need to be clearer and much more transparent about the outcomes of a college education. That includes career readiness, but it also includes critical thinking, adaptability, and, importantly, civic engagement. We need to demonstrate that higher ed is not a luxury; it is a public good that benefits communities as well as individuals and helps advance humanity. At the same time, we need to hold ourselves accountable on affordability and access and making sure our students succeed. We are fortunate that we have a great track record here on four-year graduation rates, but we can never stop working on that. I think trust will come when we show through action and not words that we’re preparing our graduates to thrive, to contribute in meaningful ways, and to find high satisfaction in their careers. But that’ll take time.

LW: Gustavus is a Lutheran school. Your experience has been in public, secular universities. Now that you’re here, do you see a place for faith and religion on campus?

JV: Yes. We have five core values here: Excellence, Community, Justice, Service, and Faith, and that’s everywhere. We don’t shy away from these core values. At the same time, there’s no pressure on students. This is a place, where, in the Lutheran tradition of acceptance, you can come with faith, no faith — wherever you’re at — and we will accept you.

There’s a 20-minute service on Tuesday, a 20-minute service on Thursday midday, and one on Sunday afternoons that are all run by students. We have three chaplains on campus. No matter where anyone is on their own journey, they have the chance to plug in if they choose to. A lot of this is about being present and finding spirituality, whatever that may be. Christ Chapel, which is right in the center of campus, is gorgeous. And it’s open 24 hours a day. When we first moved here, I found myself going in there one evening. I pulled the door open, and there’s this little fountain running, which gives the sound of trickling water. The sun was setting, and I thought, “Wow, you can’t help but feel well here.”

LW: So you see a connection here to wellbeing?

JV: I think the faith-based dynamic gives us an extra advantage. I’ve never been at a university where we can actually talk about it, and I do think it helps, particularly if you put this in the context of community. It’s really all about relationships and connection. We’re hosting Bob Waldinger on campus next spring, and I’ve asked students, faculty, and staff to read his book “The Good Life.” Bob is the director of the longest continuously running study on what makes people happy, and at the end of the day, it’s relationships. In a very intentional way, I want to bring this message to campus to reinforce that element here.

LW: Do you think about how technology, particularly AI assistance and online learning options, will affect relationships between students and faculty or students with each other?

JV: I definitely think about that. And I also think it’s an opportunity for us to get ahead of it. We certainly can’t put our head in the sand, but we need to be very thoughtful about how we use technology. For the liberal arts, we need to fulfill the promise we make to families that we are institutions with high touch, smaller class sizes — all those opportunities. We have to be present. That’s our strength.

After the pandemic, there was discussion here about whether we should continue with some online courses, and my understanding is the students overwhelmingly voted no. They wanted in-person classes. What that signals to me is the students who come here want to get to know their professors, and they want to be able to be in the classroom and have those relationships.

LW: As president in a challenging time for higher education, how do you “lead” through it?

JV: It is tricky, for sure, because you are in some ways the main translator for your college. You are one that sets the tone and delivers the message, and there’s a real balance to uphold. You have to help bolster morale in very difficult times, but you don’t want to come off as Pollyannaish. You need to be authentic and truthful. This is a hard time for higher ed. There’s a real assault on academic freedom and a misunderstanding of what academic freedom really is. It’s our mandate as leaders to be supportive of and consistent with the values of academic freedom and open inquiry, but it’s very challenging. We just have to keep moving forward.

You can reach LearningWell Editor Marjorie Malpiede at mmalpiede@learningwellmag.org with comments, ideas, or tips.

A Creative Conversation

David Kelley is the Donald W. Whittier Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Stanford University, but most know him as the creator of the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, or simply the d.school. Kelley, who celebrates 50 years at Stanford this year (as both student and professor), presents more like an eloquent historian than an engineering genius. But it should be no surprise that the founder of an institute that invented “outside the box” thinking would be such fun to talk with.

The founder of design firm IDEO and recipient of numerous honors and awards, Kelley describes his work as“helping people gain confidence in their creative abilities.” He and his brother are the authors of “Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within Us All.” In it, they argue that labeling people, particularly children, as creative or non-creative is as limiting as it is incorrect. In this interview with LearningWell, Kelley talks about the connection between creativity and discovery, how human-centered design is changing the world, and how the d.school got its name.

LW: I’m very curious about one of the main focuses of your book, which is creative confidence — unleashing the creative potential within us all. What do you think the implications of that idea are in the context of higher education?

DK: Most of my work could be categorized as helping people gain confidence in their creative ability. That would be what I care about the most. And I think we start out by people thinking of themselves as not creative, and I’ve tried to convince people — and prove — that everybody’s wildly creative. They just have blocks in the way of it. So you need to change the mindset from teaching people to be creative to giving them credit that they’re already a creative organism and remove the blocks keeping them from doing that. The psychologists call it self-efficacy — that you believe that you can accomplish what you set out to do. I mean, that’s just it. Wouldn’t you like to give every one of your students the notion that they can accomplish what they set out to do and have that confidence? I really think that’s the goal here.

So how do you go about that? The way you go about it, especially with students, is to help them have some success. You set it up so that it’s a problem that’s easily solved, and you hold people’s hands, and you lead them through it, and they’re successful at some small thing. Then you do another one, and then you do another one. Pretty soon, people are saying, “Oh my god, I am creative.” So I guess I’ll summarize: The main thing about creative confidence is how you help people remove those blocks. And the main reason that they have that block is that they are worried about the judgment of others.

LW: And that has something to do, I imagine, with what they’ve been told they are, right?

DK: Yes. You do something that’s not conventionally creative, or just doesn’t seem like it has a direction that’s creative, and then pretty soon you’re “not creative.” And people hear that when they’re nine years old. They hear, “You’re not creative,” and then they never address it again. It’s like, you try to play the piano, and you’re not good when you sit down for the first three seconds. You are not good at playing the piano, so you don’t continue. It’s hard. Doing things that matter is hard.

“The main thing about creative confidence is how you help people remove those blocks. And the main reason that they have that block is that they are worried about the judgment of others.”

LW: So you’re encouraging people to have a wider view of creativity and what that can mean?

DK: Yes, for sure. Sometimes, early on — I’m talking about child development — creativity is defined as drawing, believe it or not. If you can’t draw well without any practice and you just don’t naturally draw well, you’re identified as not being creative. Well, maybe this person’s musically wildly creative, or maybe they’re creative in a different way. So the problem is that, whatever the conventional way of doing something, if you are off that, you’re not creative. You’re also not conventional. It’s a funny dichotomy. But the main thing, yes, is that people are branded as not creative for a bunch of reasons, and we need to see that as wrong.

LW: It sounds like there’s an urgency around this. Because if people are limited in thinking about themselves as being creative, then we have arguably less creative people. Why is it important to have more creative people?

DK: It’s only if you care about the future that you think creativity is important. That’s how you cure disease and how you make advancements in technology — is people being confident in their career ability and doing new things that change the world for the better. Our phrase that we like to use is: It’s your job to paint a picture of the future with your ideas in it. The funny thing is once you can use your creativity and paint a different picture of the future, then everybody else can have an opinion. They can help you. They build on the ideas of other people when they can visualize it — when they can see it. So that ability to visualize the future is inherently a creative task.

LW: Let me ask you a little bit about the founding of the design school. Can you just give me a quick overview of that?

DK: Back to the notion of creativity — when you have a diverse group of people, you come up with better ideas. You can define diversity in any way you want: age diversity, racial diversity, or geographic diversity. But having those people — the mashup of those different people that come from different viewpoints — greatly increases the probability of you coming up with something new to the world. So that’s something I wanted to codify at the university.

And so basically the notion of the d.school was to have a place that everybody wants to come to. A lot of the classes students take in college are required classes, and so the teacher doesn’t really want to teach them, and the students really don’t want to be there. I wanted a place where everybody wanted to be there all the time — that they opted into this place because it was so enjoyable, so fulfilling, rewarding, informative. So the d.school is really based on that notion of making a crossroads, where professors and students from all over the university would come together. And I’m so gratified. It turned out so great. And the reason — they all say the same thing, particularly the professors: “When I cross the threshold, I know I’m allowed to act differently here.” And that’s just like music to my heart.

LW: Was it a difficult concept to communicate within the school?

DK: It started out with a bunch of us in a room talking. It wasn’t going anywhere particularly, but it got started. And then, fortunately, as we went further along, we had a perfect storm of administration. So we had a department chair and a dean and a provost and a president that all resonated with the idea. It took giving us the donation. I don’t know that I ever would’ve gotten it started if it hadn’t been for the generous donation from Hasso Plattner. But the president, John Hennessy, came to me and said, “What would it take for all Stanford students to be more creative — to be more confident in their creative ability?”

It really helped to have that. I mean, faculty are very siloed and more concerned about their little empire than somebody else’s. So getting everybody’s attention was difficult. It took a long time to get the place up and running to the point that people were drawn there naturally. But it did snowball. It accelerated beyond my wildest dreams because it turned out to be true — that it was super interesting for these geniuses from different departments to get together and duke it out on different topics. They really liked being there. They liked teaching together. And the way we used to do it before was I’d go in and lecture in somebody else’s class, or they’d come in my class and give a lecture. But that’s not a collaboration. Once people started to team-teach classes — somebody from political science teaching with somebody from the ed school or the business school or the law school — when they were actually standing in front of the class together for the whole class, then we knew we had it. That’s what we were after.

On a side note, one of the most interesting things that happened was how much the students loved watching the faculty fight. Somehow it was really cathartic for the students. They were used to the sage-on-stage, saying their point of view unchecked by anybody else in the room. So as soon as you get a couple of strong-willed experts in the room talking about a subject and they disagree, it’s really interesting. I think, for the students, the faculty became more human to them, and maybe there’s not a direct, correct answer to every question.

LW: I hear there is an interesting story about the naming of the school?

DK: Actually, it is not a school at all. It’s completely separate from the academic hierarchy. I remember sitting around a room — a couple of my graduate students and friends — and we were figuring out how to make this happen. And it wasn’t clear. We are a small organization and felt we weren’t very well understood. So there was the business school — the “B-school” — that was a really big deal on campus, and to feed off their importance, we decided to call ourselves the d.school.

LW: That’s fantastic! Can you define for our readers what you would call design thinking?

DK: Yeah. Design thinking is just a description of the methodology and process that we use to routinely innovate. The way I talk about it is mostly around human-centered design. So there’s plenty of people who have methodologies that are business-based or technology-based, and those are all good, and we employ those. But we seemed to lack a human-centered approach. What’s feasible and viable is nice, but what’s desirable? How do you make it more useful or convenient for people? How does it fit better into people’s lives? To me, that’s what design thinking is. It’s a human-centered approach. And all the discussion about design thinking is the steps — the methodology — that you use to do that, but it’s all centered on: How do you make it better for people?

LW: What has been the reaction to this method at the d.school from the students?

DK: Well, at first, all of our classes were electives. So the students were choosing something that they were particularly interested in. And by having different faculty, there were two wildly different points of view in the same room. So the students were excited about that. I’m going to go back to the same thing about human-centered design: Everybody can buy into this because it’s so human. I mean, we’re all humans, and the driving force is: How is this going to be better for the students? Or how is this going to be better for the people we’re trying to design something for? That humanness is just really enjoyable.

And today, one of the consequences is that I used to be able to tell the students to design a clock radio or something like that. I’d be shot if I said something like that now. They want to do something that has social value. They want all their projects to be something that’s good for the world. And I think that’s a consequence of the human-centered approach. What they want to do is improve the lives of people who live in a village somewhere and don’t have the internet. As a steady diet, that’s what they really want to do, which is encouraging for that whole generation if you ask me.

LW: You’ve been at this a long time. Any other observations about how your field has changed?

DK: Design was just not a big deal in the world as a discipline. I always say I felt like I was at the kids’ table, and then through mine and a lot of other people’s efforts, we’re now at the adult table. And I think that has to do with our way of thinking — that finding the right problem to work on is as important as the problem we are solving. Before our language, everything was problem solving, problem solving, problem solving. And after design started to take off, it was all: What’s a project worth working on? Need-finding, more than just problem solving. So that put it front and center: the messiness of trying to understand what people really want, what would make their lives better.

Part of everybody’s process now is this human-centered approach where you go out and try to understand — we call it the need-finding —what’s valuable to people. It’s a messy phase. At most companies, people want to sit there and look at their laptops in a conference room. They don’t want to go out into the field and experience what’s really going on with people. And I don’t understand why that is, but we’re getting better and better in that more and more organizations start out by trying to understand what’s a good problem to work on by understanding what people really want. And I think that’s a consequence of design having more agency in the world.

And I can tell you a million stories. One of the ones that comes to mind with my students is this class called “Liberation Technologies.” They were asked to look at fire prevention in these villages in Africa, and I thought they would end up doing a low cost fire extinguisher. But when they got down there and used our process and talked to the people, they started to realize that, yes, they were afraid of fires, but they’re really afraid of losing their documents in the fire — their immigration documents that prove they were allowed to be in this building. And so students changed the problem from fire prevention to document preservation.

Their solution was a pickup truck with a scanner in it. And they went from village to village and scanned everybody’s documents and put them up in the cloud. When you have a mindset of understanding what’s the real problem by talking to people, then you solve the problem in a completely different way or you even solve a different problem. But for your question, I think that’s the contribution of design being in the world and our methodology having some impact.

LW: Do you worry about people making things that aren’t good for the world?

DK: We used to teach an ethics class and now there’s ethics in every class — to try to understand the consequences of what you’re going to do. We have a culture of prototyping, where we take a first pass at what we’re going to make, and then you take it out and actually get it into the situation where it’s going to be used. So before you’ve committed to what it’s going to be and get it out there, you’ve seen the consequences of it. Before you commit to doing something bad or something good, you want to know the non-obvious things that are going to happen when that invention enters the world.

You can reach LearningWell Editor Marjorie Malpiede at mmalpiede@learningwellmag.org with comments, ideas, or tips.

Disrupting, Politely

The New Model Institute for Technology and Engineering (NMITE) in western England offers an unorthodox approach to university life and learning by any standard. In the United Kingdom, where tradition reigns in higher education and has for several hundred years, NMITE President and Chief Executive James Newby says the fresh concept behind his college is especially radical.

Around 2021, when NMITE welcomed its first class of students, Newby joined the team of what he calls “closet revolutionaries,” dedicated to forming a new generation of engineers uniquely prepared for career. The approach centers highly practical, collaborative assignments that mimic dynamics in the workplace. The intimate, immersive, and accelerated pathway attracts a wide range of students, all hungry to get the most out of their education — and their money.

With LearningWell, Newby discusses the big idea behind NMITE and the many small deviations from the standard that bring it to life. He’s leading with the “politeness” to navigate British education from the inside and the boldness to envision how one institution could launch a movement.

LW: Tell us a bit about the concept behind your work and its history. Why is this new approach important right now?

JN: NMITE is a very rare thing in the U.K. higher education system — a new university starting entirely from scratch. It’s very unusual in the U.K. for new universities to happen at all, but to happen without evolving from some precursor institution is incredibly rare.

There are really two key strands to our mission. The first is that the U.K. engineering employers have, for about 20 or 30 years, been complaining that the graduates they get from the traditional higher education sector just aren’t what they need — don’t have the right skills. They’re not ready to work. It takes too much time, too much money, and too much effort to convert them into really good, valuable employees. So we wanted to create a university that would just prepare a different type of engineering graduate, and our key focus was to make those graduates work-ready. It’s not just about producing brains on a stick or graduates who are good at winning pub quizzes. They need to be able to work and interact and understand what they’re doing.

The second key strand of the mission was to put a university in a part of the country in the U.K. where there hasn’t been one before and, therefore, where very few young people went to university. When I explain this to Americans, they’re always very surprised because we always look like such a small country from the American vantage point. But there’s such significant regional variation in the U.K. that we feel like a number of very different countries all crammed onto this very small island. So the part of the U.K. that we’re in near Wales is very sparsely populated, and, actually, very few young people who grow up in this part of the U.K. will ever go to university and enjoy all the life benefits that come from having that level of education. There’s just a lack of ambition regionally. There’s a lack of pathways that are really clear and easy to access for young people here. So we wanted to create a new type of engineer and really warm up this higher education cold spot in the U.K.

Those are the two things we were set up to do. It’s fair to say it took a long, long time to get us off the ground. We knew we didn’t want to create something that would just add more capacity to an already quite crowded higher education sector. It had to be different. We had to be quite disruptive — in as positive a way as we can — to a sector in the U.K. that had really not undergone any kind of major reform, any structural reform for generations. Most young people in the U.K. who go off to university to do a degree do it in the same institutions in the same kind of way that they’ve always done it. Every other sector of our economy has been completely reformed in the last 30 or 40 years through market disruption or political prioritization. But higher education has largely grumbled on in the same way.

LW: Was the prospect of leading that sort of rare change in U.K. higher education what personally compelled you to get involved with NMITE? What stage in your career were you at when you joined the team?

JN: I had been working in a big, traditional university — the sort I’ve been describing in disparaging terms. So I was probably part of the problem. But I was approached and asked whether I might be interested in this really mad idea of building a new university. It was one of those questions where you think, If I say no now and then just go and do another job similar to what I’ve been doing for the last few years and just plop on through to retirement in that way, then I’ll just regret for the rest of my time that I never did this. So I took the plunge and did it. I’ve never regretted it.

We tend to attract staff who are sort of “closet revolutionaries.” They’re really frustrated by the system they feel stuck in, and they really want to do something exciting and different. Even if it might fail, you just want to do it. Or we recruit people who just don’t come from the same traditional background. A lot of our team are early career academics, so they’re in their late twenties, perhaps postdoctoral students. They’re not embedded in academic traditions. They’re good at innovation.

I lived near London when I joined. I was in the part of the U.K. where all the economic activity and the main jobs are, and all the innovation is. So I did have to grapple with moving my family to this rural corner of the country to do this. That was not an easy decision, frankly. I remember it because it’s the decision we ask a lot of our students to take when they come from London or Birmingham or Manchester. It gives you empathy, if you just remember how you felt. So I did it, and I can tell them it is the best thing I ever did, and they should give it a try. And when you’re 18, you should do things like that. You should take a few risks.

LW: So despite being positioned to bring in a new type of student in its rural area, NMITE also serves students from far and wide?

JN: It’s both. The U.K. system actually isn’t as regionally rooted as the American system. Most of our institutions have a national outlook and a national focus, whatever the location of their campus. Some of the smaller ones, just by virtue of their geography, do tend to recruit more local students. And there’s a trend towards attending your local university slightly more than there used to be, but that’s because it’s so much less expensive to do that than to have to pay for accommodation at some distant institution. And that’s another reason why well-off kids can make all the choices that they want to make and less well-off kids simply don’t have the same choices. That’s something else we’ve always been conscious of. We want to drive social mobility and give opportunities — the same kind of opportunities for the same kind of quality — to kids who generally can’t move around the country just because of economic constraints. Our split between local students and those recruited nationally is about 40-60 in favor of national students, but 40 percent is a significant minority in the U.K.

LW: Got it. Can you elaborate on some of the other specific ways you’re flipping the script on educational tradition in the U.K.?

JN: Well, the model is distinctive in the following ways: We adopt block learning. Our students learn one topic at a time in the form of an immersive learning experience in a single module. That’s unusual in the U.K. Generally, degrees are built from various modules of building blocks, but you’ll learn them in a timetable that moves you around the campus from one topic to another in any given week. It’s a very inefficient way of learning. I often draw the comparison to learning to play the piano. You learn much quicker if you spend three weeks doing it in a completely immersive way with a full-time tutor teaching you the whole time than if you’ve split the same number of learning hours across a year and do it once a week for one hour along with everything else. That immersive form of learning significantly accelerates learning gain for students. They learn and become technically proficient much more quickly.

The other thing that’s distinctive is we accelerate the program, so we compress the learning into a shorter time period. Whereas it takes three years to do an undergraduate degree in a normal U.K. university, it only takes two years at NMITE. The reason for that is we make our students work nine to five Monday to Friday in this immersive way. That’s a much more efficient use of time. It reflects much more accurately the rhythms and patterns of a job — the workplace. It’s really good for developing a work ethic. We work very hard to make sure our students are on task for much more of the time. That means they’re working on something purposeful.

When we say that, it sounds very earnest. But we try to inject quite a lot of fun. We definitely don’t disapprove of fun. But what we really want them to be doing is meaningful, on-task work. That’s because our observation of traditional universities is students just spend an awful lot of time rattling around between lectures, not engaged in anything purposeful. And when you are paying by the year, that’s just not getting you the payback for the money you are spending. It’s just not good value for the student or the taxpayer or the university.

Our students are always working on challenge-based learning. Instead of putting them in lecture theaters and transmitting theory to them via PowerPoint presentation or a lecture, they’re working in a hands-on way. There may be a series of quite short, sharp seminars to transmit technical information, but most of the time, they’re working on something that delivers an output that reflects what happens in a workplace. They might be building a prototype or a series of codes or a circuit board. We don’t test them by traditional exams.

We’ve developed a whole pedagogical approach whereby students only succeed if the team succeeds, and they have to work in teams. We’ve designed it so you can’t possibly do the course — it’s too much — to do on your own. You could only succeed if you work as a team — divide the work up. And it’s just the social skills that develop, the extra support that inevitably provides — the nurturing that gives to people who are more neurodiverse and who struggle with self-directed learning common in traditional universities. That scaffolding is just provided in a much more real-world kind of setting. We find that’s hugely effective.

So those are the main elements of the model that are different from a traditional degree. One of the things we’re quite obsessive about is the accusation we might not be academically rigorous — that this is just too vocational in its style. We obsess about academic quality. We are absolutely determined that the students we produce will have the same level of technical knowledge and proficiency as a student from a top university. But what will be different is they’ll have much more practical capability and much more emotional intelligence.

LW: And when you heard from employers unsatisfied with newest engineers, were those the main things — work ethic, work experience — companies said young people were lacking? Are there other areas this model is directly responding to?

JN: We wanted our students to be really ethically conscious. We do that by teaching them quite a lot of liberal studies. They have to know how to do some engineering, but they have to know why they should do it — or why they should not do it.

Just being able to do something doesn’t mean it’s the right thing for you to do. We want them to understand the sociological impacts, the climate impacts — the ethical things you have to grapple with. We do a lot of work with the defense and security industry in the U.K., and that creates lots of really fascinating engineering challenges, but it creates quite a few ethical things to think about, as well. If you are building a drone, you might be building it for humanitarian purposes to deliver aid to disaster areas, but it could quite easily be repurposed to deliver munitions in a war zone. We can’t make the world simpler than it is, and we can’t make those problems go away, but we can equip students with the emotional intelligence to cope with the debate that happens around them, so they can choose where they want to apply their skills and who they want to work for.

LW: And I imagine that ethical training serves the more academic focus you were talking about, in contrast to those detractors who may say this school is totally devoted to professional development.

JN: Yeah, I’m not entirely sure how it is in the American system, but in the U.K., we have this rather tedious binary debate about vocational versus academic training. I mean, it sort of goes without saying you need both to really survive in this world and to thrive in this world. You have to be good at the practical teamworking elements, but you have to have good theoretical knowledge, as well. We want to create students who can think and do — not one or the other. We try not to overcompensate on the risk that we are viewed as too vocational and not academic enough. But on the other hand, we try not to say we’re one or the other or that one is more important than the other. The whole point is you can only succeed if you’ve led them both and produce people with genuine intellectual intelligence but practical and emotional intelligence, too.

LW: How does NMITE differ from other schools in terms of its criteria related to math and science?

JN: That was a really important thing when we started. So to do an undergraduate engineering degree in the U.K., it’s nearly always a prerequisite that you have a maths or physics A-level. An A-level is an advanced level of pre-university study, and to get a maths A-level is quite hard. It’s one of the hardest pre-university subjects you could do. Physics is hard, as well. And because they’re difficult, fewer kids do them than really should. But what we found when we were developing the NMITE courses was that most of what you need for that maths A-level doesn’t actually present until much later on — year two or year three. So we asked ourselves the question: Why do we exclude people from engineering because they don’t have that maths A-level, when they actually don’t need the content in the maths A-level until at least a year into the course? That would give us plenty of time to get them up to speed — recover their maths learning — and it would stop us having to exclude them from becoming an engineer. But if we did that, we would open up the profession of engineering to this fantastically new pool of people who are currently excluded.

Would you believe that includes an awful lot of women because women don’t do engineering in the U.K. in anything like the numbers they do in other countries? About 15 percent of engineers in the U.K. are female. So there’s a massive diversity problem. Most engineers look and sound like me — not enough females, not enough from different backgrounds, and not enough ethnicity in the profession. We wanted to focus on was the gender problem: Can we set a target to have 50 percent of our cohort as female, so that when we recruit a girl onto our courses, we don’t put her in a class with 28 other boys, so she just feels like a minority the minute she walks in the door? What we found was bright girls in the U.K. who do maths A-level almost never go into engineering. They go into medicine and other disciplines. But actually, girls who don’t do the maths A-level quite like going into engineering. We’ve got quite a lot, and they’ve really thrived.

We tracked the attainment – their mathematical and their other attainment – and we found that students with the maths A-level perform at a higher level than those without in the first year of the program, as you might expect. They’ve had better academic preparation. But by the middle of the second year, they perform at exactly the same level. The playing field is leveled, and that’s because their attainment is being tested on engineering progress, not mathematics progress. You don’t need the maths A-level. You do need maths, but you need it in a way we’re teaching it. There is no reason for universities to exclude people because of the certificates they hold.

LW: Moving to the student life side of things, you said you’re not an “anti-fun.” I imagine that’s in the classroom and outside the classroom, but what does student life look like holistically at NMITE?

JN: NMITE is right for a certain type of student. We are not right for everybody. That’s the first thing. We don’t claim to have all the answers or to be the model that will replace all other models. We are right for students who value working in a smaller institution, where everybody knows each other’s name. We want our students to know that they matter and to feel like they matter. They’re not a statistic or a number in a big cohort. Most of them will say they really like just the personal nurturing atmosphere that the small teams and the smallness of the institution brings.

Most of them like the fact that they’re kept busy and on-task, especially if you are slightly socially awkward or shy. And for a lot of neurodiverse kids, it often presents as a kind of social awkwardness or a difficulty in forming connections and relationships. They do well here because they can work in a small team that isn’t scary or intimidating. It feels quite nurturing and after a period of time, they gain quite a lot of social confidence from being able to practice in the safe place that a small team provides. So we are often struck by the fact that some of our kids join us without being able to even look you in the eye or talk to you properly. And then by the end of the course, they’re like George Clooney. They’ve got all this charisma and this confidence. That’s the transformational change that we really see.

The students that this isn’t right for are the ones like, frankly, my two sons, who want to go to a big city, where there’s loads of social things to do and sports facilities and bars and restaurants and thousands of other students and loads of clubs you can join. We are not the right institution for students who want to do that.

LW: Right. Is it a challenge to attract students who maybe didn’t see college on their path, even if the school is in their backyard — to get them to see this as an option and to come?

JN: It was a real challenge to start with. It’s becoming a smaller challenge as we go, the more we deliver good results. We’ve now got a graduated cohort of students out in the workplace. Our first-ever intake has gone all the way through and has now left – finished, graduated – and they’re in the workplace. That’s enormously helpful to telling people, “This could be you.” That’s reflected by our application rates, which are very strongly up. But to start with, that was really difficult. Our opening pitch was, “Come to a university you’ve never heard of in a part of the country you’ve never heard of to do a degree that’s really hard and no one wants to do. How ‘bout it?”

LW: On that note, what is the buzz like in the engineering community around this program? Are you seeing a lot of students who were once planning on a traditional path but then looked at this model and said, “Wow, this is a lot more interesting”?

JN: We get a lot of those. A lot of our students could have chosen any university in the country. They have the means and the academic preparation to do that. A lot wouldn’t have been given a second glance by the traditional system, but a lot could have. And the buzz from the employers is just fantastic. It’s very important we work closely with employers in our challenge-based learning in our studios. That’s an important part of our model. Employers are embedded in our curriculum in a way they’re not anywhere else, and there’s a bit of altruism involved. A lot of employers just wanted to get involved with this really interesting experiment in higher education. But now we’ve got employers who want to join because they know the graduates are so work-ready — so capable — by the end of their course that they want to get in early so they can pick them off before they get picked off by some other employer. So most — in fact all — of our first cohort of graduates got jobs before they graduated, and most of them got those jobs from partners they’d worked with during the course. They just formed those relationships. That’s a key part of the model. It smooths the transition from university to work. It’s not a completely continuous transition, but it’s very close to it.

LW: And what might you be looking forward to from here on?

JN: Because we’re small by design, our aim is not to grow bigger and bigger and bigger and then dilute the model, as we start reverting to the sameness of the sector. But we do think there’s an opportunity, at least in this country, to replicate the model. It can become a kind of surgical intervention in areas that are economically disadvantaged because we’re a small, quite agile university. So instead of the normal hundreds of millions of dollars or pounds it would take to build an academic infrastructure that universities normally involve, we see ourselves as a small, modular, nuclear reactor that could be put into an area, and then it can just warm it up. It creates new jobs — creates more knowledge-based jobs — which is hugely important, and it creates more really good opportunities for a professional, rewarding, economically secure life for kids who would otherwise never have the opportunity to do that.

You can reach LearningWell Reporter Mollie Ames at mames@learningwellmag.org with comments, ideas, or tips.

Beyond Expectations

Donatus Nnani remembers being “utterly unprepared” for the first college he attended. After leaving school and serving in the military for five years, he decided to try again, this time at Austin Community College (A.C.C.), where an unusual seminar would change his life and his confidence as a student.

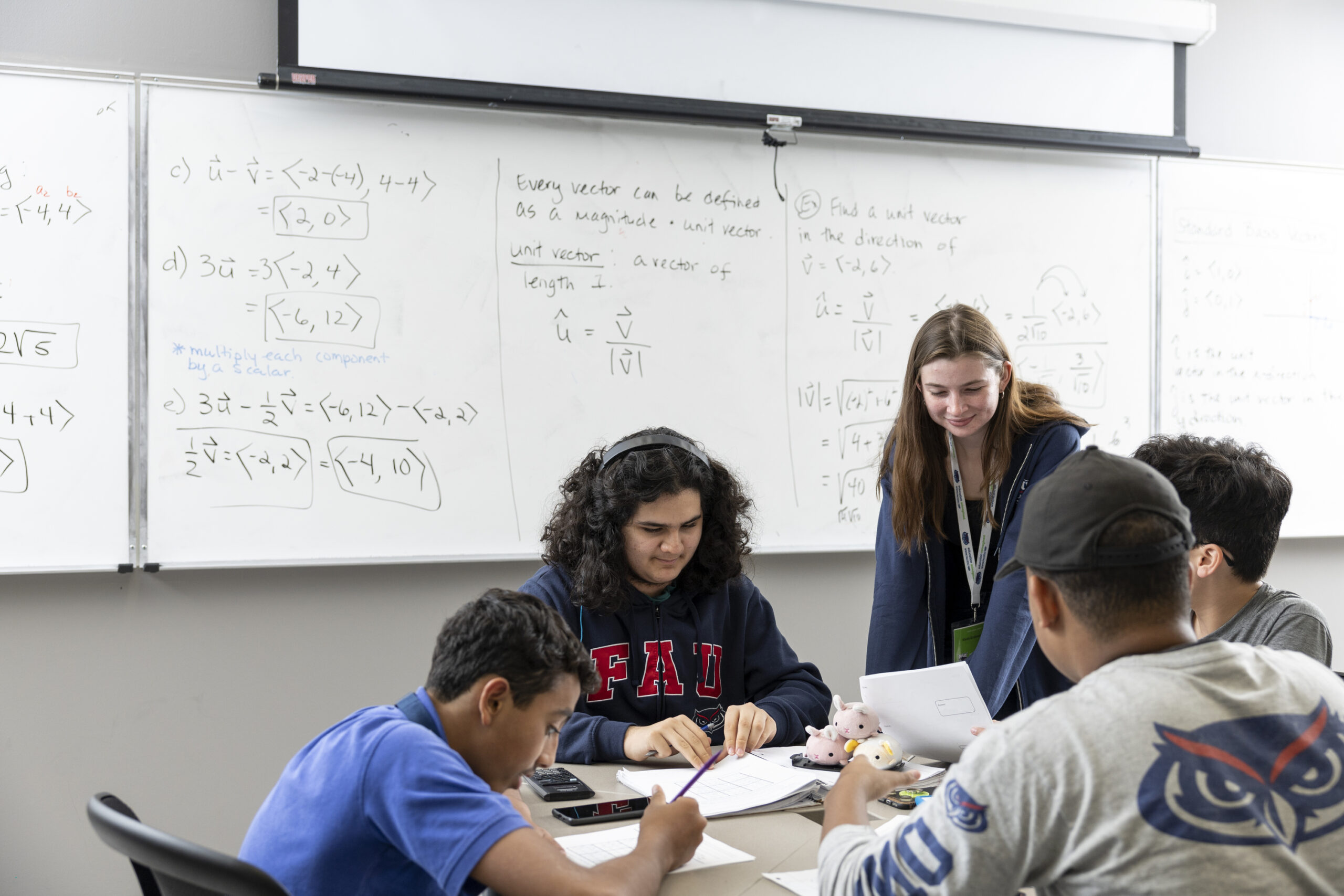

Nnani was one of the first students to enroll in the Texas college’s Great Questions Seminar, a discussion-based, first-year course in which students mine for meaning and relevance in renown texts, ranging from Homer’s “The Odyssey” and Euclid’s “Elements” to global religious texts and Chinese poetry. By design, Great Questions resembles a liberal arts class at any college or university, complete with students sitting in semi-circle and faculty strolling the room.

“Great Questions was very different in the sense that it treated students as if they were already in a university setting,” said Nnani, who graduated from A.C.C. and went on to earn a bachelor’s and master’s degree from the University of Texas, Austin. “You were expected to engage with and dissect this work on a level that isn’t always typical in community college.”

Challenging community college students to reach beyond what is expected of them is an impassioned goal of the seminar’s creator, Ted Hadzi-Antich Jr., associate professor of government at A.C.C. and founder of the Great Questions Project. Educated at St. John’s College in the Great Books method, Hadzi-Antich believes exploring the wisdom associated with life’s biggest questions is exactly the right introduction to higher education for all students.

“We’re talking about big concepts and looking at them from very different perspectives,” he said. “We’re reading epic poetry and studying religious texts. We’re seeing the ways the questions are raised in different times and places. What is justice? What is beauty?”

Hadzi-Antich’s effort to infuse a liberal arts pedagogy into a community college setting has become a personal and professional quest and, at times, “a bloody battle.” In addition to the Great Questions Seminar, he developed the Great Questions Journey, a pathway that applies a similar core-text and discussion-based learning format to a variety of courses within general education at A.C.C. Hadzi-Antich has also launched the Great Questions Foundation, whose programs include curriculum redesign institutes that train faculty throughout the country in the Great Questions pedagogy.

“We’re talking about big concepts and looking at them from very different perspectives. We’re reading epic poetry and studying religious texts.”

But with powerful forces pushing for job training and skills-based learning over broad education, particularly in community colleges, Hadzi-Antich and his colleagues are working against a strong tide. And yet, they make a case that community colleges are the future of the liberal arts. They cite positive outcomes reported by Great Questions students, such as increases in retention and transfers to four-year institutions. Their biggest challenge may be getting higher education to rid itself of an unhelpful mindset: underestimating the intellectual curiosity of community college students.

The Power of Questioning

Well before he created the Great Questions Seminar, Hadzi-Antich was fresh out of school and teaching a class on Texas politics at a community college. “It was kind of boring. It was boring for me, and it was boring for my students,” he said. To mix things up, he assigned Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America” and watched the class come alive.

“It was obvious these kids could read serious stuff,” he said.

Hadzi-Antich never went back to lecture-style teaching but kept his head down amidst colleagues who followed a more traditional format. At A.C.C., he saw an opening to bring a great books seminar concept to the multi-campus institution within its required, first-year student success offering. But securing the opportunity to introduce first-year students to a radically different educational experience was hard-won.

“I remember some administrators at the time saying, ‘I don’t think that community college students can handle that kind of curriculum, and that just gave me this kind of righteous anger,’” he said.

First launched as a pilot funded by the institution, the Great Questions Seminar would be an alternative to the other required student success course, an educational psychology class focused on effective learning. A collegial competition emerged, and remains, between the tracks, with Hadzi-Antich believing that a seminar that stimulates intellectual curiosity by exploring life’s most fundamental questions is the obvious choice.

“We looked at this and said, ‘We’re teaching students to be effective at learning, but higher education is about more than optimizing your efficiency in downloading information into your brain,‘” he said. “It’s about developing as an individual and figuring out how to live a good life.”

The Great Questions Seminar pilot, which ran from 2015 to 2017, produced impressive quantitative and qualitative data. Semester to semester persistence rates of students who took the seminar were 92 percent, with 73 percent of students who persisted earning a G.P.A. of 3.0 or above. In a video for the Teagle Foundation, which provided a grant to support implementation at A.C.C. past the pilot stage, students referred to the course as “empowering” and “life-changing,” with one young woman saying, “I felt the courage in my own voice.”

“You got to witness real transformation among students,” said Nnani, who is now the director of operations at the Great Questions Foundation. “Some people went from being shy, introverted, and not very confident in their ability to speak, coming forth with intelligent, insightful opinions. And more importantly, they knew it.”

Gaining confidence in critical thinking is at the heart of the Great Questions Seminar. Students consider ancient texts through the lens of fundamental questions they have about the world today. The inter-disciplinary faculty are not trained as experts on the texts but act as “engaged amateurs” to facilitate what is presented as a forum among equals.

With the success of the seminar, Hadzi-Antich developed the Great Questions Journey, a pathway in general education at A.C.C. with redesigned curriculum focused on transformative texts and ideas. With the Journey program, students can engage in a discussion-based version of a variety of courses, including U.S. history, mathematics, and theater arts.

“We’re trying to take these general education courses and make them as meaningful as possible,” Hadzi-Antich said. “We want education to be something that really matters to people, not just something you check off in order to survive in this economy.”

To date, over 7,000 students have participated in either the Great Questions Seminar or the Journey classes. 140 faculty members have been trained in the standardized syllabus. The first-years that choose Great Questions for their student success requirement are more likely to transfer to four-year institutions.

For Hadzi-Antich, the most compelling evidence of the success of the Great Questions method is the fact that well after some class meetings end, groups of students linger in the hallway discussing the topic.

American Spaces

In 2019, Hadzi-Antich founded a non-profit to receive grant money for a variety of causes, from food at student events to a fellowship program for faculty throughout the country. The Great Questions Foundation has become a national convenor for the growing number of leaders who share Hadzi-Antich’s belief that discussion-based curriculum should intentionally include community college students, a cohort who make up almost half of all American college students.

Larry Galizio is president and C.E.O. of the Community College League of California, which represents one of the most established and well-regarded systems in the country. Even in a state where community college was designed as an introductory first step to higher learning, credentialing dominates. Galizio sees programs like Great Questions as important reminders of the original mission of community college: to provide a broad foundation for learning.

“There’s been a strong push in the last 15 years for shortening time to degree and getting people on a strict career pathway,” he said. “It’s very well-intentioned because community college students are often time-starved with less resources. But I think anyone in education would agree we need to educate the whole person because you’re not going to be an effective medical technician or welder unless you also know how to work collaboratively and can solve problems.”

Galizio believes perceptions based on class divisions exacerbate the push towards skills-based training over holistic education for community college students. “If you go to an elite university, there’s this expectation that your education is about discovery and you might change your major four times,” he said. “But at community college, the thought is these students just need to get their degree as quickly as possible.”

Nnani’s personal story tracks to that assumption. “As an African American man, I was taught that education was just about learning the basics,” he said. “Things like Shakespeare and Socrates, that was for white, privileged kids.” Nnami said his success as an undergraduate and graduate student disavowed him of the notion that there were two types of knowledge: “functional knowledge for poor people and abstract thinking for the privileged.”

The Great Questions Foundation is at the forefront of changing that mindset and rethinking community college as the ideal setting for the resurgence of the liberal arts. Hadzi-Antich is adamant that these ends will be achieved through the engagement of faculty, not the permission of administrators. The Foundation has trained inter-disciplinary faculty from over 60 institutions in the Great Questions method. The fellowship program, funded through a grant by the Mellon Foundation, provides stipends for 21 faculty fellows in six institutions to dig even deeper with in-person convenings, like a recent conference held at Miami Dade College.

Hadzi-Antich calls the fellowship program “the cultivation of the talent, skill, and passion to make community college the future of liberal education.” In many states like Texas, the majority of college students start out taking courses at community colleges, and younger students are pushing enrollment at many schools. Advocates see this as an opportunity to set a foundation for intellectual curiosity as well as civic engagement for a wide swath of learners.

At a time of deep polarization, higher education’s role in developing engaged citizens has been called into question. Community colleges may well step into the void.

“Higher education has a responsibility to help students understand their roles in a representative democracy and listen to the perspectives of those who are different from them,” Hadzi-Antich said. “There’s no better place to have those conversations than at a community college. They are simply the most American spaces in higher education.”

You can reach LearningWell Editor Marjorie Malpiede at mmalpiede@learningwellmag.org with comments, ideas, or tips.

Rethinking Work, Meaning, and Education

At the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minn., the question isn’t just what students will do after graduation — it’s who they’ll become, quite consciously. In an age when higher education is often measured by employment rates, St. Thomas is leaning into a different measure of success: whether students leave not just with a degree, but with a sense of purpose.

Through The Purpose Project, launching this fall, the university is reframing college as a formative journey, one in which reflection, storytelling, and ethical exploration are as essential as more traditional career prep. As the new thinking goes, if all a student takes away from college is an entrée to their first job, they — and the college — have missed the point of higher education.

“I think we fail our students if, when they graduate, all they think college was good for was getting them their first job out of college,” said Christopher Michaelson, professor of business ethics. “But,” he conceded, “we also fail them if we don’t help them get that first job.”

The heart of the new initiative sits in the juncture of that tension between the practical and the profound, at a time when the practical is increasingly under the crosshairs for “return on investment.” Part cultural philosophy, part pedagogical blueprint, The Purpose Project asks a different question than the ones colleges often lead with. The focus is not so much “What career do you want?” but instead “What kind of life are you trying to build?” And then it offers the tools for that blueprint.

From the earliest conception, the project was never meant to be a philosophical silo but a shift in the university’s core culture: a way of weaving reflection and purpose through the fabric of a student’s entire experience. Amy McDonough, chief of staff in the Office of the President, watched this idea take root in the university’s leadership and spread throughout the campus.

“We wanted this to be something that students encounter throughout their time here — not just a one-off retreat or capstone,” she said. “It’s not about putting pressure on students to ‘find their purpose’ in college. That’s too much. Instead, it’s about equipping them to begin the lifelong process of searching.”

The Purpose Project took shape with support from a Lilly Endowment grant and was further strengthened by campus-wide strategic planning, culminating in its inclusion as a priority. University President Rob Vischer allocated institutional support to the initiative, advocating that a St. Thomas education must be more than transactional.

In the process of planning, McDonough and her colleagues began an audit of what was already happening across the university. They discovered that many faculty had been doing work rooted in vocation and reflection. The task then became one of elevation: recognizing that existing work, giving it a common language, and creating a framework that could unify and strengthen it.

Around the same time, a grant through the Educating Character Initiative at Wake Forest University was also awarded to the Office of the Provost to support faculty development around the teaching of virtue and character formation. The initiative focuses on helping faculty explore how virtues such as integrity, empathy, and courage can be integrated into their teaching across disciplines. And it complements other elements of The Purpose Project by reinforcing the university’s mission to cultivate ethical leaders and graduates committed to the common good.

The touchpoints of The Purpose Project now include a reimagined First-Year Experience course that introduces students to vocational thinking from day one. Sophomore-year retreats, piloted with students from the Dougherty Family College at St. Thomas, are designed to meet students at a mid-college moment when questions of major, direction, and identity converge. For seniors, faculty are working to infuse capstones with deeper reflection on purpose.

Even techniques like storytelling, which might seem tangential to vocation, have been folded into The Purpose Project’s scope. Faculty have partnered with organizations like Narrative 4, co-founded by author Colum McCann and supported by figures like Bono and Sting, to help students tell their own stories. In telling where they’ve come from, students reflect on who they are, who they want to become, and how they want to contribute to the bigger picture.

“Students come to realize, ‘I can tell my story, and I reflect a little bit about myself.’ And then if you can carry that through, you combine that with what you’re learning and how you want to show up in the world,” McDonough said.

Still, she was quick to note that the project, with its exercises and skillsets, is meant to feel organic, not imposed. “It’s about recognizing and elevating the work that’s already happening. When you talk to alums, it’s been a distinctive piece of their education,” she said. “This isn’t about adding more to people’s plates. We’re not talking about taking on another minor. This is work that helps you reflect on the rest of your life.”

A new elective class, designed by Michaelson, the business ethics professor, is one of the most tangible expressions of The Purpose Project. Called “Work and the Good Life,” the course is launching this fall in two pilot sections. The idea had been percolating for years, grounded in Michaelson’s research and personal convictions, as well as research for his book “Is Your Work Worth It?” which explores the intersection of personal fulfillment, ethical responsibility, and professional ambition. The Purpose Project brought together a team of faculty to build the course from the ground up.

Michaelson had long been observing a tension in his students. Many were driven, focused, pragmatic — laser-aimed at securing that first job. But what many lacked, he felt, was space to ask the bigger questions: What is work for? How does it fit into a good life? What responsibilities come with privilege and education?

The course invites students into those questions. Developed with input from faculty across disciplines — chemistry, social work, English, entrepreneurship, and political science — the course is interdisciplinary and intentionally open to students from all majors. One section is dedicated to honors students; the other is open enrollment. But both sections will converge at times for plenary speakers and shared conversation.

Each week, students experience three modes of engagement: a lecture-style session, a small-group discussion, and an asynchronous reflection. Assignments are deliberately experiential and reflective. In one assignment, students interview someone whose job does not require a college degree, seeking to understand motivations and obstacles. In another, they interview a retiree to explore how perspectives on work evolve over time. Throughout, they pursue methods of creating a life path using tools from the world of design thinking, while also building an appreciation of the idea that paths rarely unfold as planned.

The culminating assignment is a letter to a “wise elder”— a parent, mentor, or imagined confidant. In it, students reflect on three fictional job offers, each with its own balance of compensation, passion, and public service. Their task is to justify, in writing, the path they feel drawn to and why. It’s a final exercise in what Michaelson called “asking better questions.”

“I’m not telling students what kind of work they should do,” he said. “I’m helping them ask better questions. That’s the real goal.”

“I’m not telling students what kind of work they should do. I’m helping them ask better questions. That’s the real goal.”

In many ways, the crux of the forward-thinking course lies in a deceptively old-school tool: a physical workbook. Unlike most contemporary digital course materials, this one is tactile. Students write by hand. They fold it open on dorm desks and coffee shop tables. Forming answers this way takes time.

“Research suggests that we learn differently when we actually write by hand,” Michaelson said. “It slows you down. It encourages reflection.”

The workbook includes single-day exercises and multi-part projects, but perhaps its most endearing quality is its intentional tone. Michaelson likened it to the Dr. Seuss book “My Book About Me,” a fill-in-the-blank childhood journal filled with drawings and declarative statements. (“My favorite food is macaroni and cheese! When I grow up I want to be an astronaut!”)

Michaelson’s own children had copies, and years later, enjoyed the glimpses of their past selves. That’s the spirit he hopes this workbook captures: not to infantilize students, but to offer a keepsake of where they were at this moment in life.

“I hope years from now,” he said, “they look back and say, ‘That’s what I thought I wanted… and here’s what I’ve learned since.’”

It’s all part of the focus on intentional work — with an eye to giving back. While some programs and institutions stress an element of being the best X you can be, St. Thomas, as a school founded in a faith tradition, believes in going a step further and linking your goals towards larger obligation.

“We don’t say, ‘You can be anything you want to be.’ If you want to be a really good bank robber, well, that might be O.K. in other places, but we’re more judgy than that,” McDonough laughed. “We say, ‘You can be anything you want to be — for the common good.’ It’s also about what you’re bringing to the world. That’s a distinction here.”

Hear Their Voices

Nichole Hastings called her experience navigating college a “trial by fire.”

As a student with cerebral palsy and autism, she found the small, private institution she chose near home in upstate New York didn’t have a background supporting learners with her disabilities. As a result, she said, her time in school often involved “more advocacy than education.” It was a constant job to arrange and maintain the systems she needed to graduate — to strike a balance between necessary accommodations and room for independence.

More than 20 years after Hastings graduated, the barriers to getting to and through higher education for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities persist. She now helps run a public speaking course to prepare and promote the voices of current students who, like her, beat the odds and made it to college. The class from the Westchester Institute for Human Development (WIHD) in New York aims to make the path to post-secondary programs more visible and accessible to students of all abilities by elevating real-life stories, while equipping those who tell them with valuable communication and advocacy skills.

Mariela Adams, a program manager at WIHD, which provides resources to people with intellectual disabilities at all life stages, developed the public speaking course, inspired in large part by her experience caring for a son who is nonverbal due to profound autism.

Her son’s inability to vocalize what it’s like living with his disability has made Adams sensitive to the importance of hearing from those who can. “When I’m working with students,” she said, “there are times when I think if my son could speak, this might be what he would say to me.”

Adams’ role at WIHD had been to be “an agent of sorts,” she said, identifying and connecting people with intellectual disabilities to speaking opportunities. But as she found herself returning to the same presenters and presentations time and again, she began thinking about how to develop a larger network.

Building a new cohort of speakers by teaching them the communication skills herself seemed like a promising way forward. From tutoring individuals one-on-one, she teamed up with Think College, an advocacy organization for inclusive higher education programs, to develop a group course.

“We just really are connected to that mission that the most impactful way of understanding what it is like to be a person with intellectual disability pursuing a college degree is by listening to them,” Adams said of her alignment with Think College.

Think College’s purpose — to connect students with intellectual disabilities to post-secondary education — stems from a recognition of what the programs can offer them. As of 2022, only about two percent of those with intellectual disabilities who graduated high school were likely to attend college, even though the majority of those who did found competitive employment, higher wages, and mentorship on the other side.

So far, Adams has run the public speaking course twice remotely over the summer for students from all around the country and once in-person for students at InclusiveU, a program for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities at Syracuse University.

In the ten-session summer courses, students learn to develop their own unique presentation, starting by exploring the audience they want to reach and the topic they’re interested in covering and moving into content development and practicing in front of peers.

The initial classes in which students decide on their subject are key, Adams said, because the more passionate they are about it, the more powerful their presentations are likely to be. “That’s my sort of guiding principle. It’s got to come from where they’re at, what’s relevant to them,” she said.

The students craft strong messages based on their own experiences. Some have opted to address medical professionals and first responders, while others have targeted parents, educators, or administrators. Students have covered what to know about having a service animal in college, trying to build friendships and social connections, and needing to use a communication device when speaking becomes difficult.

Adams realizes that, while ideally empowering, opening up about these challenges can be anxiety provoking. “I really want to help them see that them sharing their lived experience can lead to significant change,” Adams said. “I also want them to see that they’re giving a lot of themselves, and I want to recognize that — that sharing your lived experience can also put you in a really vulnerable spot.”

One protective measure Adams encourages is for students to find the presentation style that makes them most comfortable, whether academic or humorous, data- or visuals-based. That way, the talks unfold on their terms.

The group format of the class is also helpful, as students can derive motivation and inspiration from their peers, all tasked with the same challenge.

In general, Adams tries to balance pushing students to move through the scarier parts of public speaking and offering them the support they need. “I think that we can do a lot by teaching students that even the greatest public speakers, they work a lot on their craft,” she said. “It may not feel great when you first start doing it, but you can always get better.”

Nichole Hastings joined the teaching team as a co-facilitator in part to be a model for students to see that people with disabilities can be successful both in higher education and as advocates and public speakers.

“I can show them that, yes, I’ve been where you’re at. I’ve been through post-secondary education programs as an individual with a disability, and it’s not an easy road, but if you want to pursue it, you can,” Hastings said.

During one summer session, a student with cerebral palsy, like Hastings, arrived at the second day of class and announced, “I can’t do this.” His frustrations with needing to use a communication device, which often prompted people to cut him off or not let him finish his thoughts, had become overwhelming.

“I know what I want to say, but people just don’t let me get out,” the student told Hastings. “They don’t let me be the person that I am because I have to use a device and I have cerebral palsy and they see my physical disability first.”

Hastings assured him that the instructors and students in the class would give him “the time, the space, the respect, everything you need to be able to do what you need to do here.”

From there, building awareness around communication devices and how to respond to those who use them became the heart of the presentation the student devised and Hastings coached him through.

“The reason why I do what I do and I love what I do is because once people find their voice and they find out how it can be used and how it can be heard, they grow by leaps and bounds,” Hastings said. “I’ve seen it.”

“Once people find their voice and they find out how it can be used and how it can be heard, they grow by leaps and bounds.”

Grace Medina, who is visually and hearing impaired due to a rare congenital condition called Goldenhar syndrome, came to Adams’ course after a previous public speaking opportunity, her first, opened her eyes to her own untapped talents.

“I was on a panel, and I was super, super nervous, did not think that I could do it,” Medina said. “And then once I got up there, and I had the mic, I was like, ‘Oh, I could do this all day. I love this.’”

At that point, she was a sophomore at Sooner Works, a four-year certificate program at the University of Oklahoma for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

After the panel gig, Medina enrolled in Adams’ speaking course. In the beginning, she found herself rambling off topic while presenting and running out of time before making all her points. Adams helped her organize the content and manage time.

Medina was also able to pinpoint her preferred communication style, which she said is “more lighthearted and funny” for the sake of audience members, especially those with disabilities who might be easily overwhelmed.

Since graduating from her program at O.U. in May 2024, Medina has started teaching at a pre-school for children with special needs, while continuing to pursue public speaking and serving as a peer mentor to students in Adams’ class.

This spring, she was the keynote speaker at a conference focused on inclusive post-secondary education and described the challenges and triumphs of her journey through college, particularly with a service dog, Velvet, by her side.

For Adams, the goal moving forward is to continue supporting former students, like Medina, already on the public speaking circuit, as well as reach new ones perhaps yet to discover a knack for presenting.

While funding changes at Think College mean Adams’ course didn’t run this summer, she’s anticipating another version this fall in partnership with U.I. Reach, a program for students with intellectual disabilities at the University of Iowa.