Donatus Nnani remembers being “utterly unprepared” for the first college he attended. After leaving school and serving in the military for five years, he decided to try again, this time at Austin Community College (A.C.C.), where an unusual seminar would change his life and his confidence as a student.

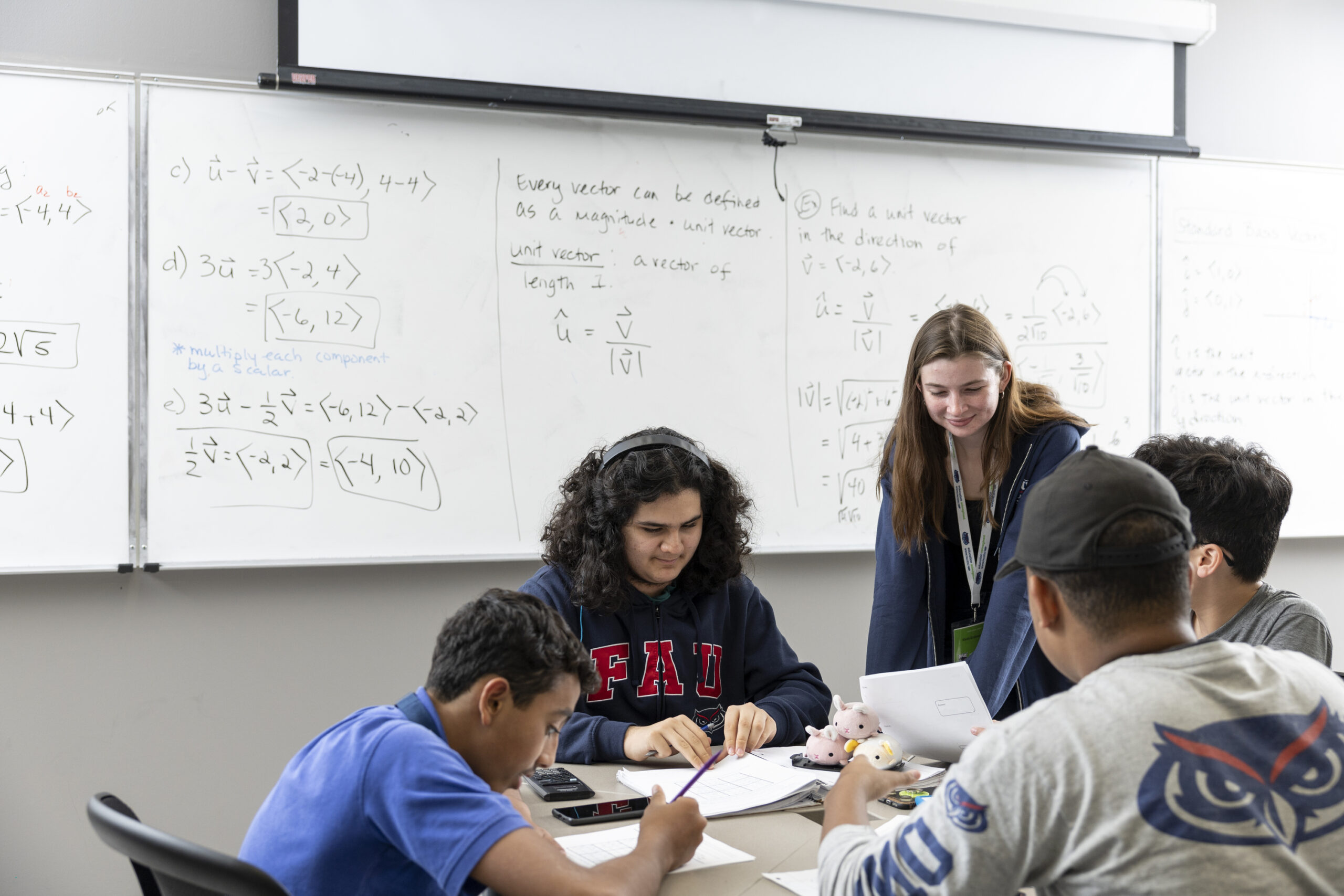

Nnani was one of the first students to enroll in the Texas college’s Great Questions Seminar, a discussion-based, first-year course in which students mine for meaning and relevance in renown texts, ranging from Homer’s “The Odyssey” and Euclid’s “Elements” to global religious texts and Chinese poetry. By design, Great Questions resembles a liberal arts class at any college or university, complete with students sitting in semi-circle and faculty strolling the room.

“Great Questions was very different in the sense that it treated students as if they were already in a university setting,” said Nnani, who graduated from A.C.C. and went on to earn a bachelor’s and master’s degree from the University of Texas, Austin. “You were expected to engage with and dissect this work on a level that isn’t always typical in community college.”

Challenging community college students to reach beyond what is expected of them is an impassioned goal of the seminar’s creator, Ted Hadzi-Antich Jr., associate professor of government at A.C.C. and founder of the Great Questions Project. Educated at St. John’s College in the Great Books method, Hadzi-Antich believes exploring the wisdom associated with life’s biggest questions is exactly the right introduction to higher education for all students.

“We’re talking about big concepts and looking at them from very different perspectives,” he said. “We’re reading epic poetry and studying religious texts. We’re seeing the ways the questions are raised in different times and places. What is justice? What is beauty?”

Hadzi-Antich’s effort to infuse a liberal arts pedagogy into a community college setting has become a personal and professional quest and, at times, “a bloody battle.” In addition to the Great Questions Seminar, he developed the Great Questions Journey, a pathway that applies a similar core-text and discussion-based learning format to a variety of courses within general education at A.C.C. Hadzi-Antich has also launched the Great Questions Foundation, whose programs include curriculum redesign institutes that train faculty throughout the country in the Great Questions pedagogy.

“We’re talking about big concepts and looking at them from very different perspectives. We’re reading epic poetry and studying religious texts.”

But with powerful forces pushing for job training and skills-based learning over broad education, particularly in community colleges, Hadzi-Antich and his colleagues are working against a strong tide. And yet, they make a case that community colleges are the future of the liberal arts. They cite positive outcomes reported by Great Questions students, such as increases in retention and transfers to four-year institutions. Their biggest challenge may be getting higher education to rid itself of an unhelpful mindset: underestimating the intellectual curiosity of community college students.

The Power of Questioning

Well before he created the Great Questions Seminar, Hadzi-Antich was fresh out of school and teaching a class on Texas politics at a community college. “It was kind of boring. It was boring for me, and it was boring for my students,” he said. To mix things up, he assigned Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America” and watched the class come alive.

“It was obvious these kids could read serious stuff,” he said.

Hadzi-Antich never went back to lecture-style teaching but kept his head down amidst colleagues who followed a more traditional format. At A.C.C., he saw an opening to bring a great books seminar concept to the multi-campus institution within its required, first-year student success offering. But securing the opportunity to introduce first-year students to a radically different educational experience was hard-won.

“I remember some administrators at the time saying, ‘I don’t think that community college students can handle that kind of curriculum, and that just gave me this kind of righteous anger,’” he said.

First launched as a pilot funded by the institution, the Great Questions Seminar would be an alternative to the other required student success course, an educational psychology class focused on effective learning. A collegial competition emerged, and remains, between the tracks, with Hadzi-Antich believing that a seminar that stimulates intellectual curiosity by exploring life’s most fundamental questions is the obvious choice.

“We looked at this and said, ‘We’re teaching students to be effective at learning, but higher education is about more than optimizing your efficiency in downloading information into your brain,‘” he said. “It’s about developing as an individual and figuring out how to live a good life.”

The Great Questions Seminar pilot, which ran from 2015 to 2017, produced impressive quantitative and qualitative data. Semester to semester persistence rates of students who took the seminar were 92 percent, with 73 percent of students who persisted earning a G.P.A. of 3.0 or above. In a video for the Teagle Foundation, which provided a grant to support implementation at A.C.C. past the pilot stage, students referred to the course as “empowering” and “life-changing,” with one young woman saying, “I felt the courage in my own voice.”

“You got to witness real transformation among students,” said Nnani, who is now the director of operations at the Great Questions Foundation. “Some people went from being shy, introverted, and not very confident in their ability to speak, coming forth with intelligent, insightful opinions. And more importantly, they knew it.”

Gaining confidence in critical thinking is at the heart of the Great Questions Seminar. Students consider ancient texts through the lens of fundamental questions they have about the world today. The inter-disciplinary faculty are not trained as experts on the texts but act as “engaged amateurs” to facilitate what is presented as a forum among equals.

With the success of the seminar, Hadzi-Antich developed the Great Questions Journey, a pathway in general education at A.C.C. with redesigned curriculum focused on transformative texts and ideas. With the Journey program, students can engage in a discussion-based version of a variety of courses, including U.S. history, mathematics, and theater arts.

“We’re trying to take these general education courses and make them as meaningful as possible,” Hadzi-Antich said. “We want education to be something that really matters to people, not just something you check off in order to survive in this economy.”

To date, over 7,000 students have participated in either the Great Questions Seminar or the Journey classes. 140 faculty members have been trained in the standardized syllabus. The first-years that choose Great Questions for their student success requirement are more likely to transfer to four-year institutions.

For Hadzi-Antich, the most compelling evidence of the success of the Great Questions method is the fact that well after some class meetings end, groups of students linger in the hallway discussing the topic.

American Spaces

In 2019, Hadzi-Antich founded a non-profit to receive grant money for a variety of causes, from food at student events to a fellowship program for faculty throughout the country. The Great Questions Foundation has become a national convenor for the growing number of leaders who share Hadzi-Antich’s belief that discussion-based curriculum should intentionally include community college students, a cohort who make up almost half of all American college students.

Larry Galizio is president and C.E.O. of the Community College League of California, which represents one of the most established and well-regarded systems in the country. Even in a state where community college was designed as an introductory first step to higher learning, credentialing dominates. Galizio sees programs like Great Questions as important reminders of the original mission of community college: to provide a broad foundation for learning.

“There’s been a strong push in the last 15 years for shortening time to degree and getting people on a strict career pathway,” he said. “It’s very well-intentioned because community college students are often time-starved with less resources. But I think anyone in education would agree we need to educate the whole person because you’re not going to be an effective medical technician or welder unless you also know how to work collaboratively and can solve problems.”

Galizio believes perceptions based on class divisions exacerbate the push towards skills-based training over holistic education for community college students. “If you go to an elite university, there’s this expectation that your education is about discovery and you might change your major four times,” he said. “But at community college, the thought is these students just need to get their degree as quickly as possible.”

Nnani’s personal story tracks to that assumption. “As an African American man, I was taught that education was just about learning the basics,” he said. “Things like Shakespeare and Socrates, that was for white, privileged kids.” Nnami said his success as an undergraduate and graduate student disavowed him of the notion that there were two types of knowledge: “functional knowledge for poor people and abstract thinking for the privileged.”

The Great Questions Foundation is at the forefront of changing that mindset and rethinking community college as the ideal setting for the resurgence of the liberal arts. Hadzi-Antich is adamant that these ends will be achieved through the engagement of faculty, not the permission of administrators. The Foundation has trained inter-disciplinary faculty from over 60 institutions in the Great Questions method. The fellowship program, funded through a grant by the Mellon Foundation, provides stipends for 21 faculty fellows in six institutions to dig even deeper with in-person convenings, like a recent conference held at Miami Dade College.

Hadzi-Antich calls the fellowship program “the cultivation of the talent, skill, and passion to make community college the future of liberal education.” In many states like Texas, the majority of college students start out taking courses at community colleges, and younger students are pushing enrollment at many schools. Advocates see this as an opportunity to set a foundation for intellectual curiosity as well as civic engagement for a wide swath of learners.

At a time of deep polarization, higher education’s role in developing engaged citizens has been called into question. Community colleges may well step into the void.

“Higher education has a responsibility to help students understand their roles in a representative democracy and listen to the perspectives of those who are different from them,” Hadzi-Antich said. “There’s no better place to have those conversations than at a community college. They are simply the most American spaces in higher education.”

You can reach LearningWell Editor Marjorie Malpiede at mmalpiede@learningwellmag.org with comments, ideas, or tips.