Zoe had always wanted to study abroad. When looking at colleges, she was drawn to Lehigh University because of something she saw called “Lehigh360.” As the name suggests, Lehigh360 is an institution-wide initiative that helps students see the world through a broader angle by engaging in high-impact practices, like traveling to different countries, conducting research, or working on real-world problems.

“That said to me, ‘This school cares about these experiences and the students who want to have them,’” said Zoe, now a rising junior at Lehigh who spent last summer in Africa. “Lehigh360 connected me with an amazing opportunity that literally changed my life.”

While it continues to accommodate students like Zoe who gravitate towards new experiences, Lehigh360 is also there to inspire the larger number of students who, for whatever reason, do not. Now in its third year, Lehigh360 aims to equip every student at Lehigh with the information, access, and encouragement to pursue projects or programs that can prepare them for life, as well as career. Part database, part marketing campaign, Lehigh360 seeks to fill the access gap around these opportunities by addressing a number of barriers, whether lack of awareness, affordability, or self-confidence.

“We want all students to have these kinds of transformative experiences, and we want a more democratic, egalitarian process, where any student that comes here should be able to participate in them,” said Michelle Spada, the director of Lehigh360.

Spada works within Lehigh’s Office of Creative Inquiry, where Lehigh360 was, fittingly, created. Formed out of a desire to have students work on complex problems through open-ended projects, the Office of Creative Inquiry is an academic and non-academic vehicle for digging into big global issues. Its core program is called “Impact Fellowships,” through which students work in small teams and with faculty mentors on a host of global and local issues over two semesters with two to three weeks of on-site fieldwork in the summer.

Within the Office of Creative Inquiry, Bill Whitney is assistant vice provost for experiential learning programs. Having seen the positive impact of the office’s work on students who engaged, Whitney and his colleague, Vice Provost for Creative Inquiry Khanjan Mehta, were curious about how many of the university’s students were taking advantage of similar experiences on campus. What little information they found proved disappointing. When they asked students and alumni about study abroad or leadership or mentorship opportunities, a lot of them said they hadn’t participated in them; many said they didn’t know about them at Lehigh.

“It was clear then that we needed a better way of getting all these ambitious, driven, capable students doing things that are outside of just their march to degree, as important as that is,” Whitney said. “That’s what led us to Lehigh360.”

Whitney said part of the urgency to improve access to high-impact programs and experiences stems from the evidence of their significant educational benefit. Their longer-term benefits, including helping to develop a sense of purpose and fulfillment in life and career, have broad appeal for many worried about the lack of purpose so many young people are reporting.

As strong advocates of this work, Whitney and Mehta began to convene campus stakeholders and alert them to the gap that existed in connecting students with these evidence-based practices. It was not a tough sell, given the school’s strong history of learning through doing. Best known for engineering, Lehigh’s close affiliation with Bethlehem Steel, once the anchor industry in the region, offered a host of work/learning opportunities that still exist today.

“There is a historical connection to experiential learning that I think everyone is on board with here, and there are these incredible pockets of signature high-impact opportunities,” said Whitney. “The problem is they exist in totally different spaces, and there’s no connection between them. There’s no common place to find them or learn how to get involved.”

Whitney met with over a hundred campus offices across numerous departments to achieve a significant level of buy-in for a campus-wide effort to organize and promote the many opportunities. They created a director-level position for Lehigh360 and hired Michelle Spada. Spada had previously worked on one of Lehigh’s high-impact opportunities — the Iacocca International Internship, a fully funded program for students who have some level of need — and before that, for an Africa fellowship program at Princeton University.

Spada said her previous work opened her eyes to the equity and access issues that exist in these programs. “Too often with these high-impact practices, we are just passing students back and forth — those that are really good at writing applications and presenting, those who happen to be bumping into the right people. But what about the others? Do they even know these opportunities exist or how they may get funded for them?”

Spada said the accessibility issue becomes even more pronounced considering the advantage these experiences have in today’s job market. Employers looking for distinctions beyond G.P.A. are eager to see what kinds of activities or work/learning experiences candidates have had in college. Those who decry Gen Z’s lack of readiness are likely to see working on real-world problems as a protective factor.

“When you consider that employers are putting an emphasis on these experiences, often over G.P.A., it becomes our responsibility to be much more intentional about them,” Spada said.

Lehigh360 offers a number of on-ramps to these opportunities, starting with communicating and promoting the benefits of doing something in addition to that “march to degree.” The vision for Lehigh360 is to help students find their place in the world, which includes knowing what the world needs from them. “We ask students, ‘What excites you? What really lights you up?’” Whitney said. “But we also ask, ‘What problems in the world do you want to help solve?’”

The vision for Lehigh360 is to help students find their place in the world, which includes knowing what the world needs from them.

In its most basic form, Lehigh360 is an accessible database and a toolkit that students can use to explore what opportunities exist. Students can query a number of different domains, such as travel in a certain part of the world, work internships, research opportunities, and special programs like fellowships or scholarships.

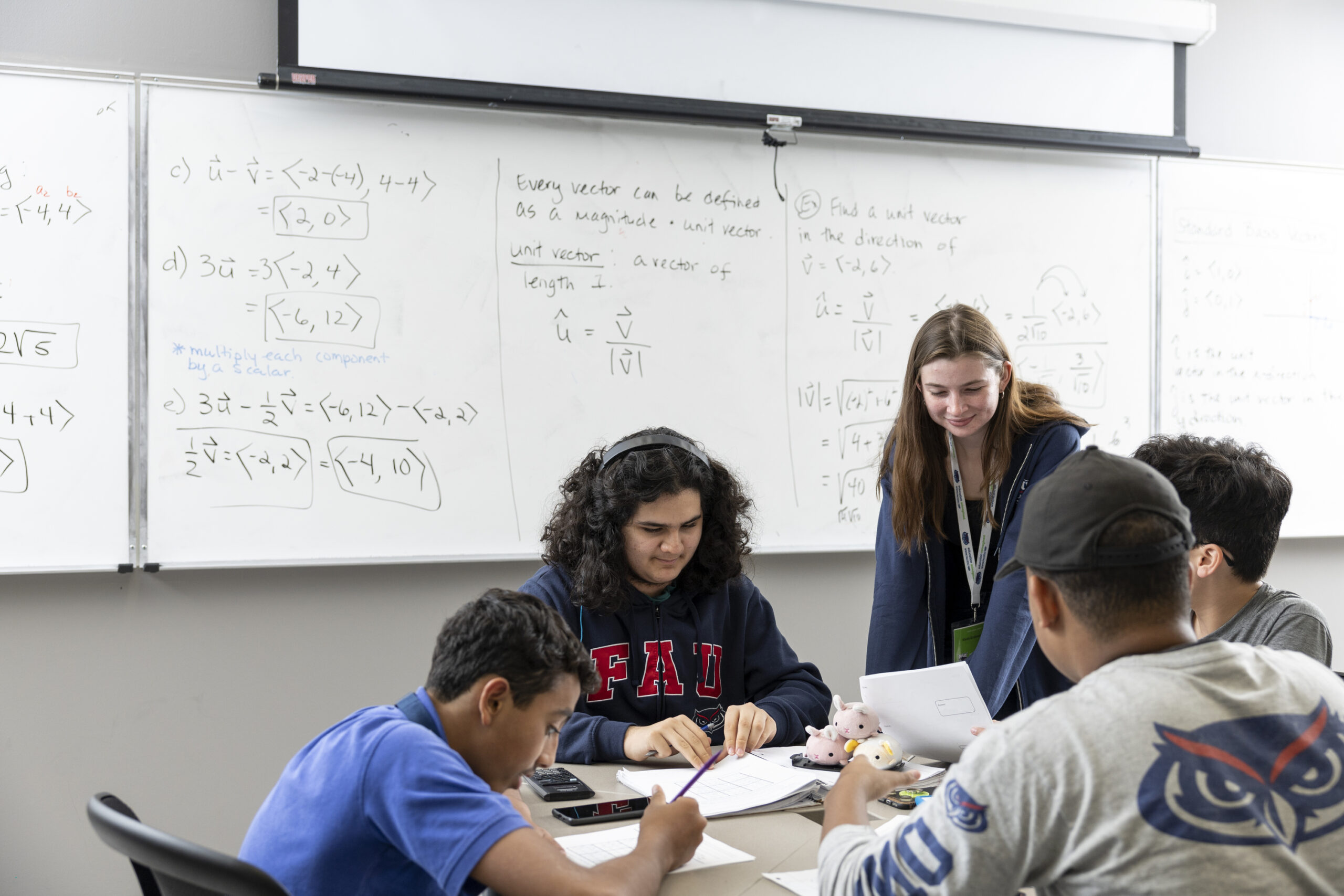

Students are introduced to Lehigh360 in their first year and reminded of opportunities through different touch points, like academic advising, student-facing services, and classroom presentations. Student “opportunity guides” help their peers with applications and references. The school even offers a pre-orientation Lehigh360 course to get students thinking about these experiences before they matriculate and to widen their perspective of what is possible.

Sometimes getting a student to participate in activities outside their comfort zone involves more than just providing good information. Roisin, a rising junior at Lehigh, is currently in Edinburgh, Scotland, working for a social enterprise that helps fund small businesses in developing countries. The two-month position follows her previous internship in Uganda, an experience she said she never would have had without Lehigh360.

“As soon as I got the internship in Uganda, I went straight to Michelle and told her how nervous I was, and she was so helpful,” Roisin said. “She told me about the good experiences other students had had with the same program and showed me the value of doing this in my first year. She told me, ‘You will learn so much, and then you can apply that in everything you do in the three years you’re back at school.’”

With Spada’s encouragement, Roisin went to Uganda, where she taught English to elementary students, taught the staff to play rugby, and met one of her best friends. “It was the best experience of my life — so far,” she said.

“My experience last summer really opened up my perspective on the world,” Roisin added. “As far as teamwork and working with people I didn’t know, I just feel like I am so much more of a well-rounded person. I think everyone should be taking advantage of opportunities like these because it has honestly changed me for the better as a person. It has affected my mental health, my happiness.”

Roisin said the equity focus of Lehigh360 is important to her. She was able to participate in part thanks to being a “Soaring Together Scholar,” which involves a full-tuition scholarship to the university and a $5,000 stipend towards an experiential learning opportunity.

Spada believes initiatives like “Soaring Together” are small first steps in addressing the financial barriers many students encounter in even considering these programs. She and Whitney are working on leveling the playing field in this regard by connecting students to funding sources and securing paid internships for students who cannot afford to give up outside employment.

An important part of the equity work involves getting a better understanding of who participates and why. Following up on Whitney’s informal inquiry regarding awareness, Spada has engaged a student research team called “Impact Trails” to do qualitative research to help answer questions, such as “How did you get involved?” and “If you are not involved, what were the biggest barriers?”

The research itself is a high-impact opportunity for students and another example of how to connect learning to doing in college. “When I hear people talk about their education, I hear a lot about wanting their classwork to translate into action and into what they may want to do for the rest of their lives,” said Taylor, a rising sophomore at Lehigh and a member of the Impact Trails team. “I wanted to conduct research, and when I learned about Lehigh360 from a presentation in my first-year engineering class, I immediately looked at those opportunities.”

As the research continues, anecdotal evidence suggests Lehigh360 is taking off. Students said most of their friends now look into opportunities on the Lehigh360 website. Alumni lament it did not exist when they were at the school. Whitney said the effort to provide a common platform for the many opportunities that exist for students has faculty and administrators eager to get their programs included.

Still, he worries Lehigh360, like many initiatives in higher education, may be viewed as the passion of one department, as opposed to the culture of the entire university. The one thing he said he does not worry about is buy-in from the students.

“The students that come here, or any university, are ready to thrive. They are ready to flourish. It’s our job to help them do that.”