When Hannah M. was a college student a few years ago, her mentor — the chair of her department — was, as she recalls, a thoughtful person who was also extraordinarily busy. “When I needed to know something about credits and certifications, she would say she’d get back to me,” Hannah said. “But she usually didn’t.” Hannah often ended up finding her own information about licensing or grants and making her own connections through LinkedIn. “I didn’t want to complain because I knew she meant well, and I had friends who didn’t have mentors at all.”

Mentorship has long been a cornerstone of youth development, but for young adults today, finding effective, supportive relationships is hit or miss. For mentors, meeting the shifting landscape of mentees’ needs can also be up to chance. According to MENTOR, a nonprofit national mentoring partnership, one in three young people grow up without a mentor figure, and those from low-income communities are even less likely to have one. This, in spite of the communication and technology advances today that surpass any other generation’s ability to make and maintain connections at a distance.

Jean Rhodes, a psychology professor at the University of Massachusetts Boston and founder of its Center for Evidence-Based Mentoring, has spent her career studying what makes mentorship effective. After publishing more than 250 peer-reviewed studies, she grew increasingly concerned that the field was stuck in outdated models. Despite decades of effort, the effect size of mentoring — the measurable impact on youth outcomes — has barely budged in 20 years.

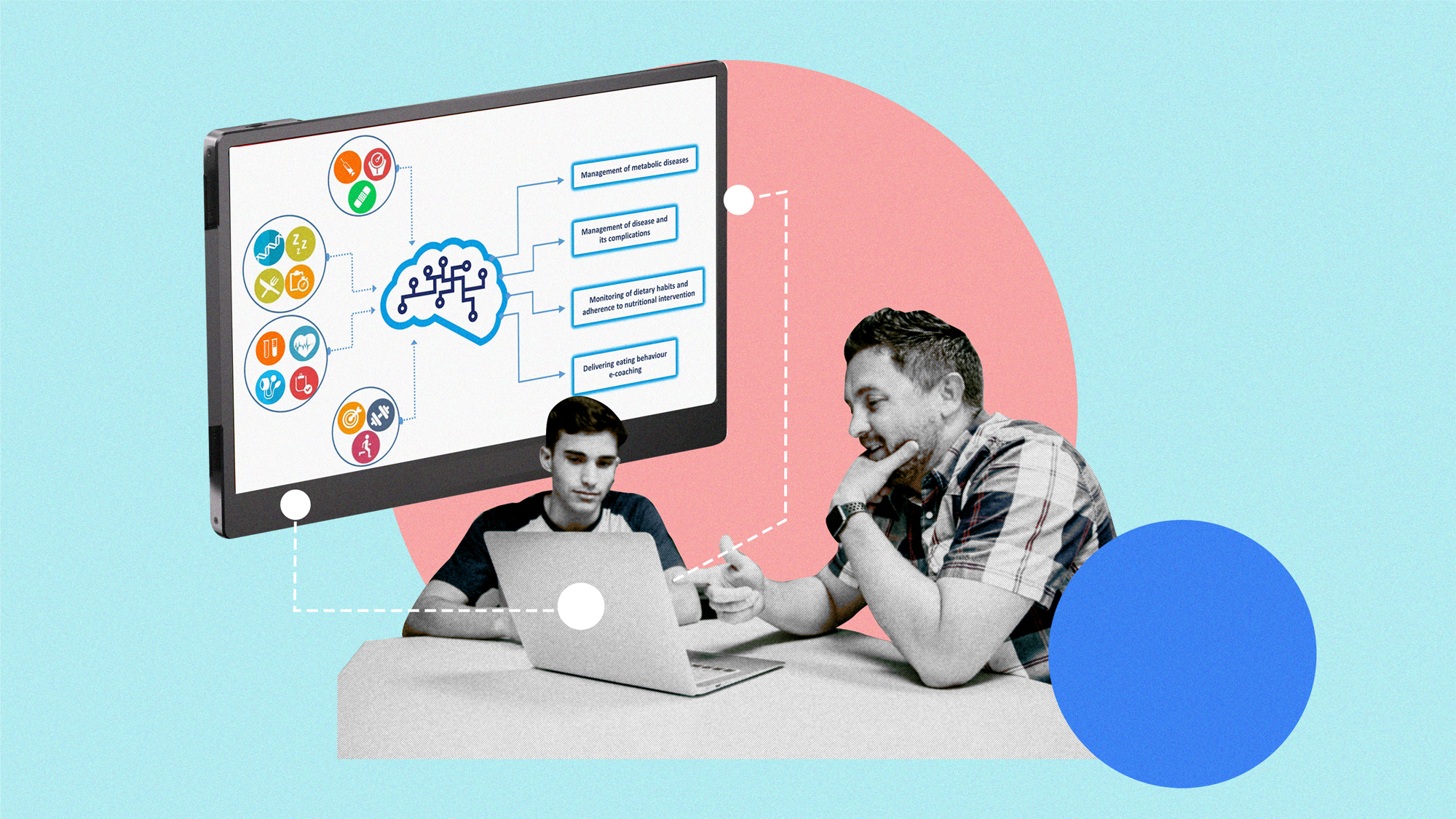

In response, she developed an A.I.-assisted platform that equips mentors with the tools, insights, and training her center has honed over the years, delivered to the palm of your hand. It isn’t intended to replace human connection but to enhance it. Rhodes describes the program as “rocket fuel for relationships” — a way to scale quality mentoring with resources at the moments they’re needed most.

The app, called MentorPRO, recently won the International Tools Competition for Higher Education, standing out among more than 1,000 entrants for its innovative approach to scaling relationships. It arrives at an odd juncture, a time when artificial intelligence is hailed as the zenith of information management, yet controversial for its role in therapeutic conversations. The fact that this advisory tool engages in both functions — information and support — is precisely what piques interest in the mentoring world. The question is: Can a tool feared to replace relationships actually make them more meaningful?

A backdrop of need: The mentoring gap

Today’s disparity between the number of young people who would benefit from a mentor and the number of adults willing and available to serve as mentors is known as the mentoring gap. There’s been a worrying decline in “naturally occurring” mentoring relationships with teachers, coaches, and neighbors, which once provided widespread support. Organic mentoring relationships are based on rapport and familiarity, says Belle Rose Ragins, a mentoring expert and professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, whose research makes the case that unless mentees have a basic relationship with their mentors, there is no discernable difference between people who have a mentor and those who don’t.

The mentoring gap was underscored by statistics from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, which reports that the number of 18 to 21 year-olds who say they’ve had a mentor has actually declined in the past decade — from about 66 percent in 2013 to 60 percent in 2022. And the mentoring opportunities that do exist are not distributed equally, often favoring those from higher-income households. The young adults most in need of mentorship — those navigating school-to-work transitions, financial pressures, mental health struggles, and social isolation — are often the least likely to receive it, the foundation found.

The Center for Evidence-Based Mentoring began to see that traditional mentoring had reached a plateau, with its measurable impact largely unchanged for more than two decades. Rhodes suspected the problem was rooted in the way we’re going about mentoring. Too often, she said, the friendship model — mentors provide companionship and a coffee date — is well-intentioned but inadequate.

“We’re still locked in friendship-based models that don’t match the complex needs of today’s young people,” Rhodes explained. “It feels good, but without training and structure, mentoring too often becomes mismatched to what mentees really need.”

This is especially true for young people grappling with major life transitions, as well as financial stress, depression, or trauma. Because most mentors are volunteers without formal training, the support they offer rarely matches the complexity of mentees’ needs. This mismatch is compounded by problems of scale and continuity: Due to constant turnover, cyclical programs and workplaces churn through new mentors without the infrastructure to sustain quality or deliver evidence-based guidance in real time. The result is a system that feels supportive but frequently fails to equip young adults with the structured, targeted help they most require.

These challenges can stifle even the most well-intentioned program. At one large community college, for example, the executive director of its alumni foundation recalled a mentor scholarship program that, she thought, had a high potential for success. It was available to both women and men, highly motivated individuals with a G.P.A. of 3.0 or higher, and those accepted into the pilot were offered free tuition as well as a $500 book stipend. Mentorship was a cornerstone of the program: Participants were assigned a mentor based on their major and career interest and required to meet at least twice a month. Yet at the end of the inaugural year, only 50 percent of participants called it a success and opted to continue working with their assigned mentor.

“I was surprised and sad to hear about the results,” said the alumni foundation director. “But in the end, it’s like speed dating. It’s only as effective as the connection with the personality on the other side of the table, which is kind of a roll of the dice if you’re assigned to one another. Add to that the expectations a mentee might end up having, and unexpected needs, and it’s a total gamble. It’s almost impossible for the mentor to be prepared for all that in advance.”

A human-centered, A.I.-supported solution

During the pandemic, mentorship turned into e-mentoring by default, while colleges and other organizations struggled to stay connected with young people virtually.

“The sudden shift to e-mentoring during the pandemic tested the capacity, professional skills, and adaptability of many mentoring programs,” concludes the MENTOR report “From Crisis into Capacity: Final Report on Findings from Recent Research on E-Mentoring,” funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. “However, these rapid innovations also fostered a belief that e-mentoring is a meaningful addition to a program’s capacity and scope, and that with proper staffing and planning time, virtual program delivery warrants further scaling.”

The Covid-19 shutdown made clearer the weaknesses that had existed in mentoring for years and provided an opportunity for virtual mentoring to step up. What virtual mentoring lacks in non-verbal cues, according to The National Institutes of Health, it gains in geographic flexibility and accessibility for a wider range of people. And that loss of in-person connection can be mitigated through intentional communication, use of video conferencing, and consistent effort from both the mentor and mentee to build a strong and supportive relationship

Rhodes began working on an A.I-enhanced platform that would step into the void, combining the flexibility of many modes of communication with the access to resources and best practices available through hundreds of pages of research. With input from her sister, a computer engineer, and support from the National Science Foundation, she designed a system that blends human-centered mentorship with A.I.’s capacity to deliver research and training in real time. As an app, it folds naturally into electronic communications. But it also serves as a genie in your pocket for information before, during, or after any kind of interactions – virtual or in-person.

MentorPRO was built in response to the shortcomings Rhodes observed in traditional mentoring. Instead of relying on casual, friendship-style interactions that may feel supportive but often fail to meet urgent needs, the platform grounds mentoring relationships in clear goals and purpose. By asking mentees to identify their priorities at the first interaction, the program helps mentors move beyond informal companionship and focus on tangible outcomes — academic progress, career readiness, or emotional wellbeing — that align with the challenges each young person experiences. This structure puts guardrails on the mentoring relationship and helps guide the partnership with growth and goals.

The first guardrail takes the form of weekly check-ins, brief surveys that ask mentees to share where they are thriving or struggling. If a mentee indicates rising distress — say, slipping into discouragement about school or career — the mentor has the chance to intervene proactively rather than react after problems escalate.

Another key feature is the platform’s ability to capture conversations and data within the app, creating a record of interactions, challenges, and progress. Instead of relying on memory or irregular check-ins, mentors and program staff have access to a growing dataset that helps track trends, tailor support, and maintain continuity even if mentors change. This addresses one of the biggest weaknesses Rhodes identified behind the effectiveness plateau: the inability of programs to sustain quality as mentors (especially peer mentors) cycle in and out. With institutional memory embedded into the system, mentees don’t have to start over if transitions occur.

Perhaps most significantly, in Rhodes’ eyes, the program addresses the training gap that has historically limited mentors’ effectiveness. Instead of front-loading generic training that may or may not be relevant later, the app delivers on-demand, evidence-based training modules at the moment they are needed. This is Rhodes’ “rocket fuel.” If a mentee discloses trauma, attention challenges, or career anxieties, the mentor is immediately provided with concise, research-backed resources — front-loaded and trained on information from the Center for Evidence-Based Mentoring — to guide the conversation. This “just-in-time” approach closes the gap between a mentor’s good intentions and actual capacity to help, transforming volunteers into skilled supporters without requiring them to become experts overnight.

Other resources synthesize useful information. Using retrieval-augmented generation models, the program scans prior conversations, mentee surveys, and local institutional resources — such as a university advising center — into short, actionable insights for the mentor. Instead of spending time trying to remember details or search for resources — like Hannah’s busy department-head mentor — mentors can focus on listening and active responses, equipped with tailored guidance automatically, without having to remember to dig later. Rhodes emphasized that the A.I. is not a replacement for human connection, but a delivery system for the research that can make it more potent.

Rhodes emphasized that the A.I. is not a replacement for human connection, but a delivery system for the research that can make it more potent.

“I created an 800-page training manual that curated all these studies and all the work that I think is really good, and I trained our language model on that,” she said. “It’s at the fingertips of a mentor right when they need it. It becomes this wonderful way to bring science and evidence into the conversations they are having with their mentors. And it makes relationships more effective without stripping them of authenticity.”

Beyond strengthening one-to-one mentoring, MentorPRO addresses another systemic weakness: the limited networks available to many young adults. Through social capital expansion and “flash mentoring,” the app connects mentees to short-term advisors in their communities — alumni, local employers, subject-matter experts — who can provide specialized guidance. This helps young adults build broader networks of support, a critical factor for career development and community integration that traditional programs often overlook.

In this way, Rhodes sought to address the systemic barriers that exist: inequitable access, lack of scalable training, poor continuity, and irrelevance to young adults’ real needs. By ensuring that mentors — not algorithms — remain at the center, while equipping them with timely, evidence-based tools, the platform helps bridge the mentoring gap.

The human at the helm

A recurring theme in Rhodes’ vision is the phrase “human at the helm.” At an age where bots have fallen short with disastrous results — say, reinforcing a youth’s suicidal ideation — the human at the helm has never been more critical. Rhodes draws a sharp contrast with A.I. chatbots marketed as companions. “Young people need to practice asking for help, navigating conflict, and building weak ties beyond their comfort zone. That’s how growth happens.” In this model, A.I. is not a substitute but a co-pilot — an invisible force making human mentors more effective, more present, and more scalable.

While A.I. can streamline, summarize, and deliver evidence, only humans can offer the sacrifice, fallibility, and authentic presence that young adults crave. They can hear and support, challenge, and engage, with spontaneous pivots to humor and flashes of reciprocity and irreverence — because that’s what it is to be human and what is rewarding about human interaction.

The MentorPRO platform is currently in place in more than 50 partnerships with higher education, youth development, and workforce development, ranging from West Point and the University of Chicago to Big Brothers Big Sisters of America and City Year to Warrior Women and the National Guard Youth Challenge. MentorPRO users report that 92 percent of mentees voluntarily downloaded and used the platform; 94 percent actively engaged with it, and 87 percent said the resources helped them achieve their goals.

Rhodes believes that structured mentoring — human relationships supported by scaffolding — can improve educational performance and workforce readiness, and wellbeing.

“Decades of research have shown that, with the right training and support, mentors and other paraprofessionals can deliver interventions just as effectively as professionals — if not more so — in ways that could help to bridge the substantial gaps in care and support,” concludes Rhodes in “The Chronicle of Evidence-Based Mentoring.” “Yet, there is a critical caveat: across all the studies comparing professionals to paraprofessionals, paraprofessionals were only effective when there was ongoing training and supervision.”