If you studied or worked at a health-promoting university, would you know it? Would you recognize the institution’s commitment to wellbeing in your daily activities, your relationships, your environment? For the colleges and universities that are part of the U.S. Health Promoting Campuses Network (USHPCN), the answer to these questions is yes, or at least, that is the aspiration.

The USHPCN is a coalition of colleges and universities dedicated to infusing health into their everyday operations, business practices, and academic mandates. It was launched in 2015 to promote the “Okanagan Charter: An International Charter for Health Promoting Universities and Colleges,” which offers a blueprint for making wellbeing an institution’s foundational principle.

As it celebrates its 10-year anniversary, the Okanagan Charter (OC) is now an institutional priority at 39 schools in the United States. Around 300 others are not official “adopters” of the charter but participate as “members” of its broader network. For these colleges and universities, the O.C. serves many purposes. It is a pledge, a road map, and in some cases, a license to experiment with new approaches outside the traditional lanes of higher education. More than anything perhaps, the Okanagan Charter is a major shift in thinking about what constitutes wellbeing on campus, as well as who is responsible.

The Okanagan Charter is a major shift in thinking about what constitutes wellbeing on campus, as well as who is responsible.

“With the Okanagan Charter, institutions around the country are reimagining higher education as a catalyst for human and planetary flourishing on every campus, everywhere,” said Sislena Grocer Ledbetter, chair of USHPCN and associate vice president of counseling health and wellbeing at Western Washington University.

International, Indigenous Origins

The Okanagan Charter reflects an international recognition of the influence of higher education on “people, place, and planet”—the three domains frequently cited within the common language the OC provides. “Higher education,” the charter goes, “plays a central role in all aspects of the development of individuals, communities, societies and cultures—locally and globally.” Indeed, colleges and universities serve as not only large institutions but major employers, creative centers of learning and research, and educators of future generations.

The OC grew out of the work of the World Health Organization’s Health Promoting Universities movement of the 1990s. The document was formally launched at a 2015 International Conference on the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus in Kelowna, Canada. The first draft of the charter was based on input from 225 people with the support of a writing team and an additional 380 delegates who critiqued and refined the document. Its introduction includes an acknowledgement that the OC was developed on the territory of the Okanagan Nation.

In addition to recognizing the influence of universities on people, place and planet, the charter’s creation and early appeal was in response to the growing international crisis in mental health. According to the Healthy Minds Study, the rate of (mental health) treatment (for college students) increased from 19% in 2007 to 34% by 2017, while the percentage of students with lifetime diagnoses increased from 22% to 36%. By 2015, it was becoming apparent that campuses in the United States were indeed not well.

One recent paper, “The Okanagan Charter to improve wellbeing in higher education: shifting the paradigm,” suggests a public health approach is the way to solve this problem which led to overwhelmed counseling resources and concerns over inconsistent help-seeking. One of the authors is Rebecca Kennedy, assistant vice president for student health and wellbeing at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the first school in the United States to sign the Charter.

“For many years now, universities have been trying to help students on their campuses thrive and flourish, increasing the availability of services on campus,” Kennedy and her co-authors explain. “Many of these services, including mental health treatment, are directed towards individuals, which is important for that individual, but does nothing to create conditions that prevent the need for these services at the population level.”

In their research, the authors found a paucity of population-based strategies and little examination on system-wide approaches. “There was little evidence of policy, systems, or settings wellbeing strategies in the higher education literature. There was a lack of scientific investigation and evaluation examining the impact of changes to public policies, regulations and laws that impact the health of college students.”

The Okanagan Charter is an effort to fill that void first by creating a framework for improved wellbeing at the population-level on campus and then capturing data that will show its effect over time. According to the charter, “Health promotion requires a positive, proactive approach, moving ‘beyond a focus on individual behaviour towards a wide range of social and environmental interventions’ that create and enhance health in settings, organizations and systems, and address health determinants.”

For colleges and universities, this means applying a “settings and systems” approach to scenarios one might think of as singular or isolated. One example the authors offer is the diet of college students. While adding more nutritional food to the dining hall menu may be one (downstream) solution to improving students’ notoriously unhealthy eating habits, keeping dining halls open and accessible after hours or during breaks so students avoid resorting to vending machines would be the upstream approach. A Campus Determinants Model, within the Okanagan Charter and mapped to person, place and planet, further demonstrates these distinctions.

Understanding What Institutional Wellbeing Looks Like

The document, which is 11 pages, provides institutions with a common vision, language, and principles on how to become health and wellbeing-promoting campuses. It includes two calls to action: “Embed health into all aspects of campus culture, across the administration, operations, and academic mandates; and lead health promotion action and collaboration locally and globally.”

What that looks like for campuses within a sector as diverse and tenuously connected as higher education is the big question and the primary work of the USHPCN. Associated with the International Health Promoting Universities & Colleges Network, the USHPCN supports campuses in interpreting and operationalizing the Okanagan Charter framework, acknowledging the unique factors that influence the OC’s adoption on each campus. Designees from the institutional members, as well as from the schools who have formally adopted the charter, work as a network, meeting regularly and sharing best practices and metrics.

Julie Edwards is the assistant vice president of student health and wellbeing at Cornell University and the chair-elect of the steering committee of the USHPCN. She is well known among the OC community, as she chairs the potential adopter cohort and is frequently called upon to consult with schools just starting their journey. She urged Cornell to adopt the Charter in 2022 and has made it a pillar of her work and that of the entire university with the full engagement of partners, from faculty members and facility managers to the president’s office.

“First and foremost, the Okanagan Charter gives us shared language and a shared vision,” Edwards said of the OC’s implementation at Cornell. “An unintended but powerful outcome is that people have become genuinely excited to understand this health-promoting concept and their role within it. Wellbeing is no longer looked at as just an initiative from Cornell Health.”

Edwards said Cornell had an existing foundation of wellbeing support for students, staff, and faculty, as well as for the planet through sustainability initiatives. The Okanagan Charter was the Venn diagram that put it all together. After the adoption of the Charter, the school created multiple guidelines that align with the guiding principles. For example, if you’re thinking of revising or creating a new policy at Cornell, you are asked to consider the question, “Is this health promoting?”

These criteria are used in decision-making throughout campus. To diffuse some of the academic stress among Cornell’s high performing students, changes have been made to transcript policies, including to avoid discriminating against students who have had to take an incomplete. Many colleges have also implemented credit caps to reduce stress of taking over 20 credits in a semester. Another recent policy change is that employees at Cornell are now allowed two additional floating holidays to use as they please.

Through the Okanagan Charter, Cornell developed a Community of Practice—a structure that Edwards describes as “bringing together diverse folks who have shared goals to work together to solve complex problems.” With the participation of about 150 people on campus, the Community of Practice is also working on assessing the impact of the policies that have been adopted.

“My hope is that when students, staff and faculty come to Cornell, they can feel a sense of care and compassion and support for their wellbeing. They can feel that they have equitable access to the services that are provided, and they are able to connect with others in meaningful ways to flourish.”

At a very different campus, the team from University of Massachusetts, Amherst is equally as enthusiastic, though less far along in the OC process. “We’ve been forming relationships, listening to speakers, really cementing the excitement for this concept as we move into implementation,” said Elizabeth Cracco, the assistant vice chancellor of campus life and wellbeing.

Cracco said the Okanagan Charter, which is now part of the university’s strategic plan, came into view after the pandemic when every stakeholder on campus focused on a common goal. “During the pandemic, there was such a great demonstration of serving the greater good of the campus, and that made us want to keep going, to keep thinking collectively around wellbeing.”

Connecting the OC’s population-based approach to student mental health is a welcome strategy for Cracco, who is a trained clinical psychologist with student counseling within her purview. She said the Okanagan Charter allowed her to add a layer to this work, expanding their existing focus on providing individual mental health support.

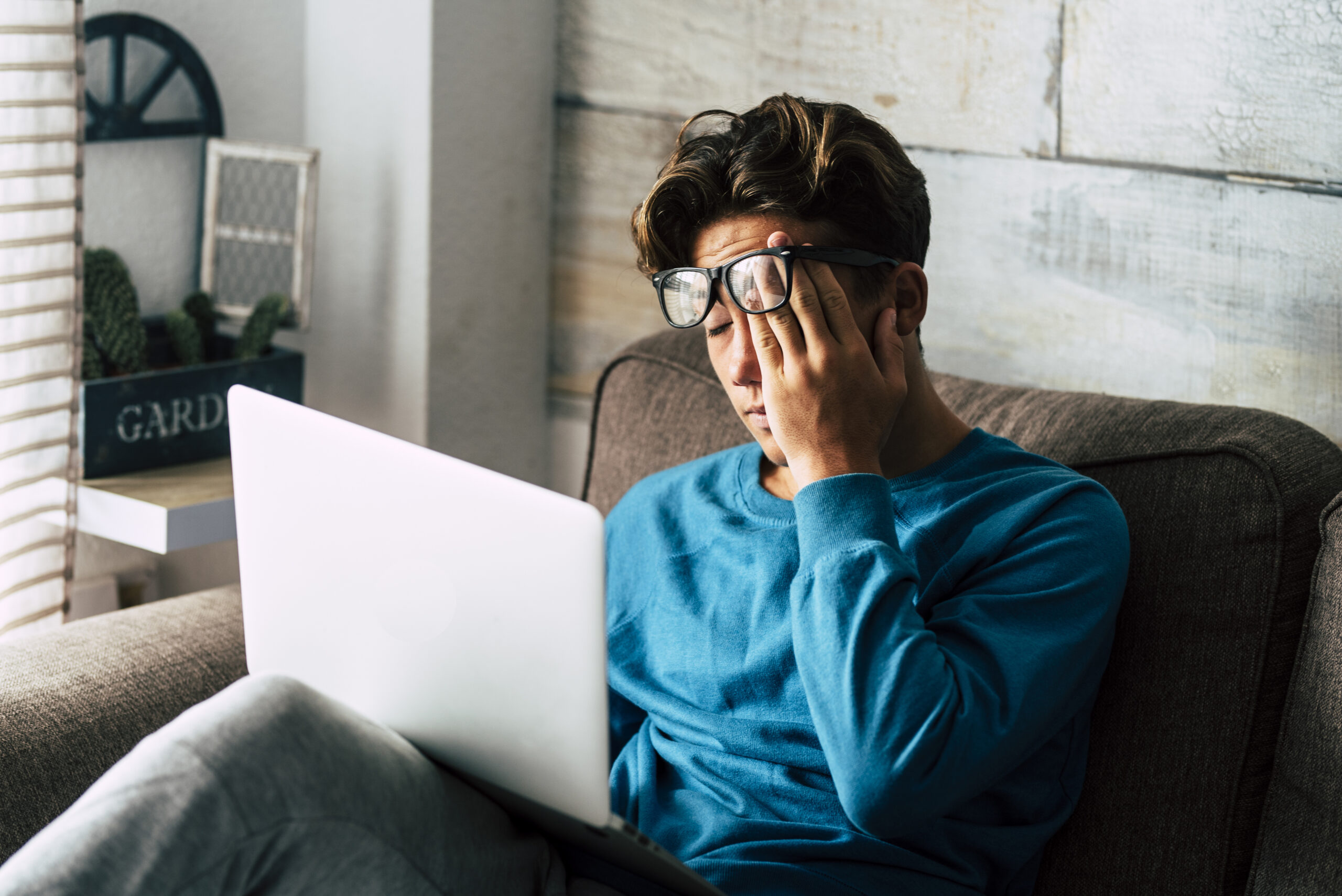

“The systems we have built to deal with students who are in distress have not gone away,” she said. “But using this collective impact framework, we are able to consider larger issues, such as, ‘How are we going to undo some of the intended or unintended consequences of everyone’s attention going to a screen instead of each other or themselves?’ That’s a whole campus problem. That’s faculty, staff and students.”

Cracco said what excites her the most about the work is the unexpected partnerships it is forging with other stakeholders on campus. As was the case during the pandemic, she is working alongside numerous teams on campus that are experimenting with new ideas, including creating a greater sense of belonging in the classroom and even making changes to the built environment. “We have a faculty member in the school of architecture who is working with her senior students on the redesign of our residence hall lounges,” Cracco said.

Cross-sector partnerships are a commonly reported benefit for schools who have adopted the Okanagan Charter. For some, like Furman University in South Carolina, the OC framework was a natural extension of what was already happening on campus. Since 2018, the school has offered the trademarked initiative “The Furman Advantage,” a student-centered pathway that requires a first- and second-year program combining academic advising and student wellbeing.

Furman’s involvement in the Okanagan Charter, first as an institutional member and then as a full adopter, was initiated by the Wellbeing Strategy Committee, co-chaired by Dean of Students Jason Cassidy and Meghan Slining, a faculty member in health sciences who is a well-known public health expert on campus.

Cassidy said he had a good feeling about the Okanagan Charter right away and appreciated being part of a learning community that the USHPCN provides.

“People from campuses all over the country are really open to sharing what they’ve done, how they’ve done it, and meeting with you one-on-one,” said Cassidy. “But there’s no playbook. They give us a unified skeleton, and then it’s up to us to put the meat on the bones that makes the most sense for our campus community. I think that’s the only way you could get something like this accomplished.”

While the adoption of the OC may have been an easy lift at Furman, it still represents a significant change in thinking on campus. Slining said she is frequently asked to explain the OC to people who, in another world, would never be expected to understand it. Their response continues to pleasantly surprise her.

“This is not business as usual where the only people who care about health and wellbeing are from the health sciences,” she said. “Centers and groups all over campus are writing the language into their mission statements and figuring out how to incorporate it into their work. They’re fired up.”