When Kylie Martin was studying abroad in Gdansk, Poland, she visited the Stutthof concentration camp with classmates. They walked the paths where victims took their last steps, and somberly regarded the piles of shoes. But the quiet detail Martin found most arresting was one that few others even noticed: In the women’s housing, wooden support beams were covered with old graffiti, messages etched in languages she couldn’t read.

“I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Here were these women experiencing genocide first-hand, yet something had moved them to carve messages on the columns. Was it an act of rebellion? A source of motivation to keep going? Or was it just a form of preservation, to nick up a beam with writing that could endure after death?” wrote Martin in the pages of her journal. As an aspiring journalist, she found herself naturally attuned to finding meaning in small details. “To me, that represented something so magnificently human — leaving behind something that’s proof to ourselves and the world, ‘I was here’.”

When she returned for her senior year at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, she was invited to share her reflections as part of the school’s new Digital Storytelling Program. The program had been launched with a grant from the Coalition for Transformational Education, designed to encourage Dearborn students to craft personal narratives in a multimedia format. It also allocated funds to hire the students to become digital storytelling mentors to other students, in turn teaching them the skills they’d learned.

Martin’s five-minute digital story included curated images of Stutthof, paired with the audio recording of her script. In its conclusion, she wondered if this was to be her role in the world — amplifying the voices of others unable to share their stories.

Using the storytelling format in an academic setting was new for her. “Digital storytelling was a method of portraying what you’ve learned that’s so much more meaningful than an academic paper. It says something very unique about the person who created it. You’re seeing a whole other side to them that you wouldn’t see if you were just reading a paper,” says Martin, who has since graduated and is working as an intern at the Detroit Free Press. “Storytelling might not come naturally or easily to some students, but it’s a strong way of getting across a message or experience. Creativity can be like a muscle — the more you work at it, the better it gets.”

The University of Michigan-Dearborn is one of a growing number of campuses recognizing the power of storytelling as a life skill worth teaching. This isn’t news for students in the arts, media, or communications, and the ability to build a compelling narrative has obvious applications and benefits across all kinds of industries — sales and marketing, law and politics, conservation and urban planning, and so on. This is what happened. This is what we need to solve. This is why it matters. In recent years, the job title “Chief Storyteller” has infiltrated the org chart in companies like Nike, Microsoft, and IBM, and narrative techniques are becoming more widely applied in STEM fields like engineering and medicine. Storytelling combines the “hard” skills of problem-solving with the “soft” skills of communication and empathy, bridging the personal and the professional. Little surprise then that campus leaders find storytelling a good tool to approach a range of important conversations including equity, career development, wellbeing, and more.

More Than a Single Story

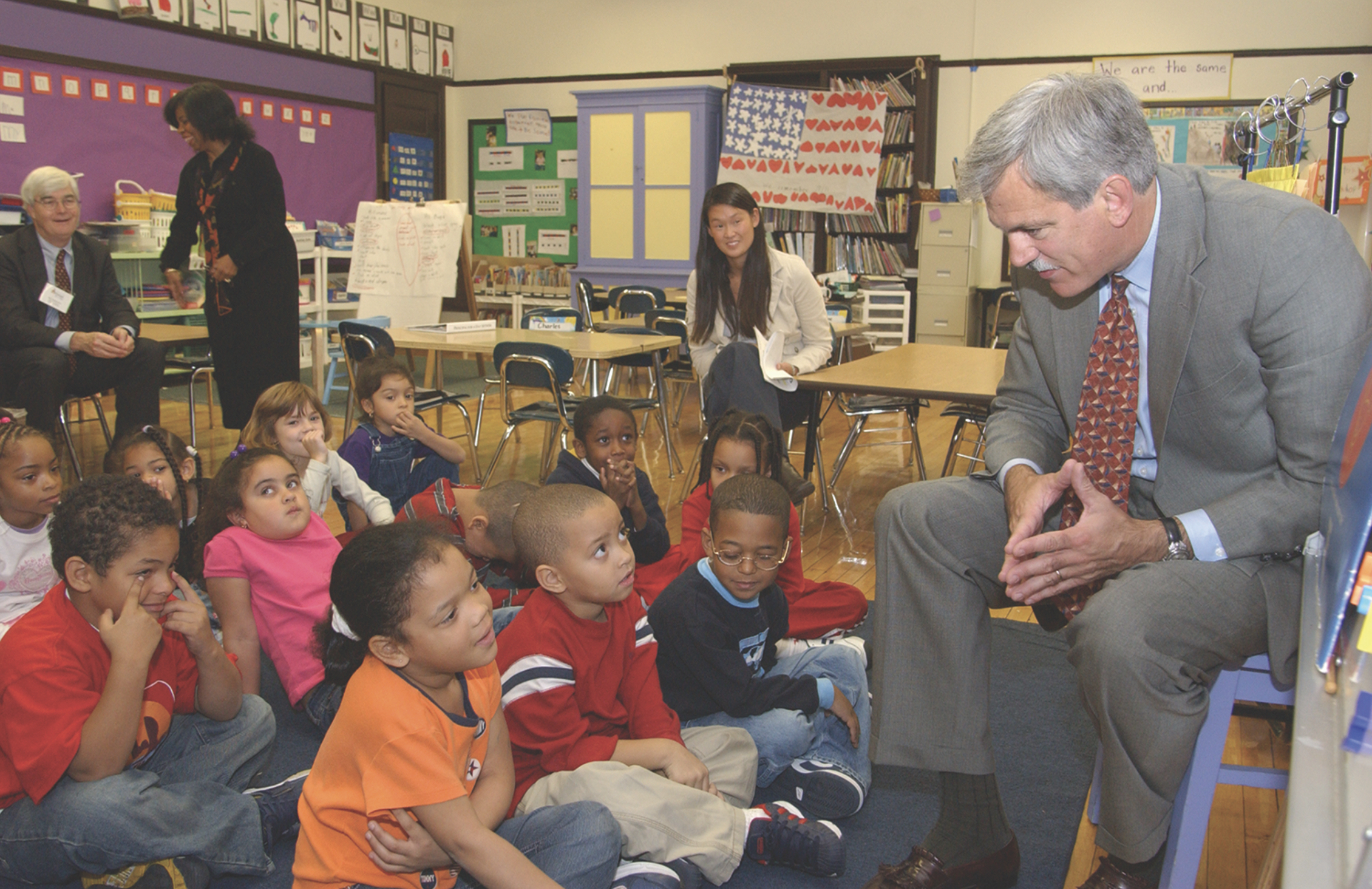

Dr. Domenico Grasso, Chancellor of the University of Michigan-Dearborn, was first intrigued by how storytelling might influence identity formation in students when he watched, and was deeply moved by, the “The Danger of a Single Story,” the TEDGlobal talk by Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Adichie. Adichie recalls arriving on campus in the U.S. and meeting her roommate, who was surprised to learn Nigerian people spoke English and listened to more than tribal music. In her talk, Adichie warns about the risk of widespread cultural misunderstanding that occurs when people make assumptions about a group of people, thinking one version of the way they live represents the narrative of an entire place.

The message made an impact on Grasso, who saw the beneficial applications for breaking down cultural misperceptions on his suburban Detroit campus. “Storytelling is the act of considering the things we take as a given and articulating them, so that they’re out in the open,” he says. “When we put into words what we assume or presume, we put it on the table to be able to talk about it.”

Dr. Grasso worked with Dr. Maureen Linker, Associate Provost and Professor of Philosophy, to create a digital storytelling project that would solicit, hire, and train students in the art of multimedia technology. After two successful cohorts of the digital storytelling project, he had an idea: What if the skills of storytelling, and the benefits of learned empathy, could be harnessed in the service of more authentic Diversity, Equity And Inclusion (DEI) initiatives?

Just last month, he revolutionized the school’s DEI process, and re-established it as the Office of Holistic Excellence. An important part of the new office’s outreach takes the form of learning about other people’s perspectives through storytelling, with a model that takes inspiration from NPR’s StoryCorps.

“The initial concept of DEI was to bring onto campus people with diverse ideas and views and origin stories,” he said. “But in our traditional DEI approach, we never asked people to tell their stories. It was enough that they checked the box, which was African-American or Hispanic or LGBTQ or veteran, and so on. And then that was it. That was where the DEI ended. We have a very diverse and heterogeneous community, but we never asked them to enrich the campus by engaging with their stories.”

In the initial digital storytelling project, as in as her philosophy classes, Linker worked with the students in the storytelling cohorts—which often began with overcoming their default mode of assuming their lives weren’t “storyworthy.”

“We have students who say, ‘Those aren’t my skills. I can’t do that.’ And we say, ‘Are you human? Then you’re a storyteller.’”

“They could look at philosophical writing from the lived experience of people on the margins, but still say their own life was not particularly interesting. And once they started working on assignments and had to share aspects of their lives, they were fascinating and complex and full of insight,” says Linker. “It has a lot to do with our demographics as a regional campus, a commuter campus. There are so many stories and perceptions of the Detroit metropolitan area. So I used Adichie’s work as a springboard for the digital storytelling project, and I was interested in having the students address and lean into the myths and stereotypes about the area and tell stories from their point of view.”

Storytelling is as old as humanity, traced back to our earliest ancestors’ campfires and cave paintings. Narratives have always been used to pass down knowledge, traditions, and culture; they make sense of the world, foster shared identities, and ensure survival. Evolutionary biologist Stephen J. Gould calls humans “primates who tell stories.”

And yet we aren’t born with the ability to tell a story; we have to acquire language to communicate, and function in social circles so we have others to communicate with. It’s a basic but critical life skill to live in community with others: persuasive storytelling compels others to partner with you, listen to your vision, and avoid the dangerous path, follow your plan. Storytelling as a genre is a broad umbrella, encompassing the skills of telling a story — the rollout and pacing of critical details, sometimes incorporating humor, culminating in a relatable larger message. But it can also mean knowing how to understand and tell your story, with the self-awareness of the personal narrative.

“We have students who say, ‘Those aren’t my skills. I can’t do that.’ And we say, ‘Are you human? Then you’re a storyteller,’” says Jonathan Adler, a psychology professor at Olin College of Engineering. Adler is also co-founder of The Story Lab at Olin, designing and coaching storytelling experiences grounded in literary practice, the performing arts, and psychological science. Beyond Olin, he also works with doctors in the Health Story Collaborative, a non-profit organization aimed at elevating personal stories in the healthcare ecosystem.

Medicine, engineering, STEM — they all rely on stories, he stresses, as much as the so-called arts. “The narrative is sort of the default mode of human cognition. Even if you’re going to spend your life writing computer code, you’ve got to be able to explain what you’re doing and why you did it that way and why it matters to the people around you. ‘Well, my goal was X, so then I did Y.’ That’s a story,” he says. “Effective communication depends on narrative fluency. And there is no profession about which you don’t have to communicate the work you’re doing.”

The narrative ecology we live in starts young. High schoolers need to tell their stories to get into college, and are asked in job interviews, Why do you want to work here? Why are you the best person for the job? Students might have spent their school years crafting persuasive academic essays. But the careers they’re entering require narrative powers of expression to put their goals in context. And sometimes they call for the self-awareness and insight to fit themselves into the story, making the case for their vision, and why they’re the person to make it happen.

“Storytelling has the potential to do something much deeper and more transformational, which is to help people articulate why they care about the things that they care about, and what they’re trying to do with their lives,” he says.

For Olin’s Story Lab, one of the key forums for students to perform their narratives is a story slam held during Candidates’ Weekend, when accepted undergraduates visit to decide whether this is the place they want to matriculate. It’s a bold move and an act of faith for the college to display these authentic voices at the same time the college admissions office is spinning its own persuasive narrative. In this context, student storytelling does more than entertain and inform with candor and empathy. It lets the listener in on the secret that it’s okay not to be perfect — to experience academic stress, social anxiety, identity confusion — which might just make Olin the perfect place to feel at home.

Adler recalls one impactful story — “a tell-without-telling story” — in which a student shares an episode of taking care of her little sister. In the course of the narrative, it becomes clear that the experience took place in the context of poverty, darker than expected, and that she was in fact only three years old trying to microwave a hot dog for a baby.

“Working with students on their stories, we’ve developed a really good attunement for what’s the right amount of vulnerability to share in a story. When it became clear that we were dealing with trauma here, it took us all by surprise, and we decided, ‘Let’s just tell the story of making the hot dog in the microwave,’” recalls Adler. “Then the story can be infused with little moments where you as the listener are like, Oh, there’s more here, it goes a lot deeper, while keeping things on this subtler level in a way that was manageable, and resulted in a really captivating story. And partly what was captivating was that you knew there were layers beneath that you weren’t getting access to.”

In this way, he helps students master this technique of understatement, telling-without-telling, to help them process the story and keep it from becoming too raw.

“And that’s what makes these experiences brilliant and beautiful. It’s a metaphoric way of thinking that I take for granted, because that’s the way I live in the world, but the students experience it for the first time as a superpower. Once they do that, it’s a skill that’s going to serve them for life, because they’re not going to need you sitting on their shoulder telling them where their metaphorical moments are like epiphanies.”

Students who gain a well-developed sense of their own story benefit from the combined biological maturity and cognitive perspective to weave together the past, present, and future —and if they’re fortunate, with humor and grace. This is particularly true of young people who dealt with trauma, or shame. The act of processing the experience — and then sharing it and being received with support and understanding — helps them better appreciate variables that were beyond their control.

“When we share our story with others, it reorganizes our experiences, makes them more categorized, and makes sense of it,” says Laura McKowen, founder of the recovery community The Luckiest Club dedicated to substance-use disorder. McKowen is a fan of storytelling because cognitively linking our life experiences — and seeing others identify with our experience — helps de-fang the otherness and humiliation. “We are meaning-making machines, and what we can’t put into a story and don’t have words for stays disorganized and festering and causes suffering and shame.”

Stories Are Pathways to Wellbeing

Will Schwalbe is a writer whose thoughtful insights into relationships characterized his 2012 memoir, The End of your Life Book Club. Last year he published a second memoir, We Should Not Be Friends, about an unlikely and lifelong relationship between him (gay theater kid) and Maxey (ebullient jock-Navy Seal) forged in a secret society at Yale in the early 1980s. This small society’s members, hand-selected for their vastly different paths in life, share awkward meals twice weekly until a capstone storytelling experience called the “audit.” Each member is given an entire evening to tell their life story — uninterrupted, for hour upon hour.

“Each drew the group closer. Most of us admitted to suffering from imposter syndrome; there was relief in that admission. Inadequacy loves company,” he wrote. “It wasn’t the stories that bound us; it was the way we framed them for one another and the fact that we shared them in the first place.”

Advocates believe students who are making this cognitive leap in understanding their own stories are far better equipped to be making new connections with others — their peers, their professors, their coaches, their future bosses, and partners. They gain insight into which of their narratives land well — humility versus grandiosity. And they become far better listeners, better able to see the meaning behind the words and stories others share and respond in a way that means more than awkward small talk. The self-aware storyteller understands that the purpose of the story is connection, not painting himself as impressive.

“If you’ve got the floor in front of a group of people and go on about how great you are, or the greatest thing you did, you would really have to find some way to couch that to make it socially acceptable. For most people who have normal situational awareness, it’s going to tamp down the urge for self-aggrandizement or to boast, because it keeps you from connecting and getting anywhere,” says Matthew Dicks, a nine-time winner of The Moth GrandSLAM (the championship round of the country’s premier live storytelling competition) and author of Storyworthy: Engage, Teach, Persuade, and Change Your Life Through the Power of Storytelling. “The need to show yourself like a perfectly curated story or Instagram post is dishonest, when you’d be better off telling a story that’s funny, with a certain amount of deprecation, or a small disaster that led to moments of realization. Better knowledge of storytelling encourages people not to share their glorified moments, because those aren’t the ones that are going to connect.”

The therapeutic value of storytelling, among emerging adults, remains one of the craft’s most important benefits. The chronic loneliness that exists for young adults today isn’t made any easier by time spent reading their phones instead of reading the room. “Storytelling forces you to make eye contact with another human being. And then they say things that make you remember things from your own life, and connect to that person,” says Dicks. “I think the value in that is enormous for people trapped on their screens all the time. It used to be pretty normal in the world for that to happen, but I think now it actually sort of has to be coached and encouraged.”

This time in late adolescence is when young adults are laying down the first version of what scientists call their narrative identity, Adler says. So for traditionally aged college students, the college experience is happening while they are in the process of laying down the first draft of their story. “And we know that draft is going to stick around and influence their wellbeing over the course of their lives.”